What should society’s resources be used for? What kinds of activities are effective, in other words, produce the best results for the well-being of people and society? How could we anticipate and prevent problems better than we do today?

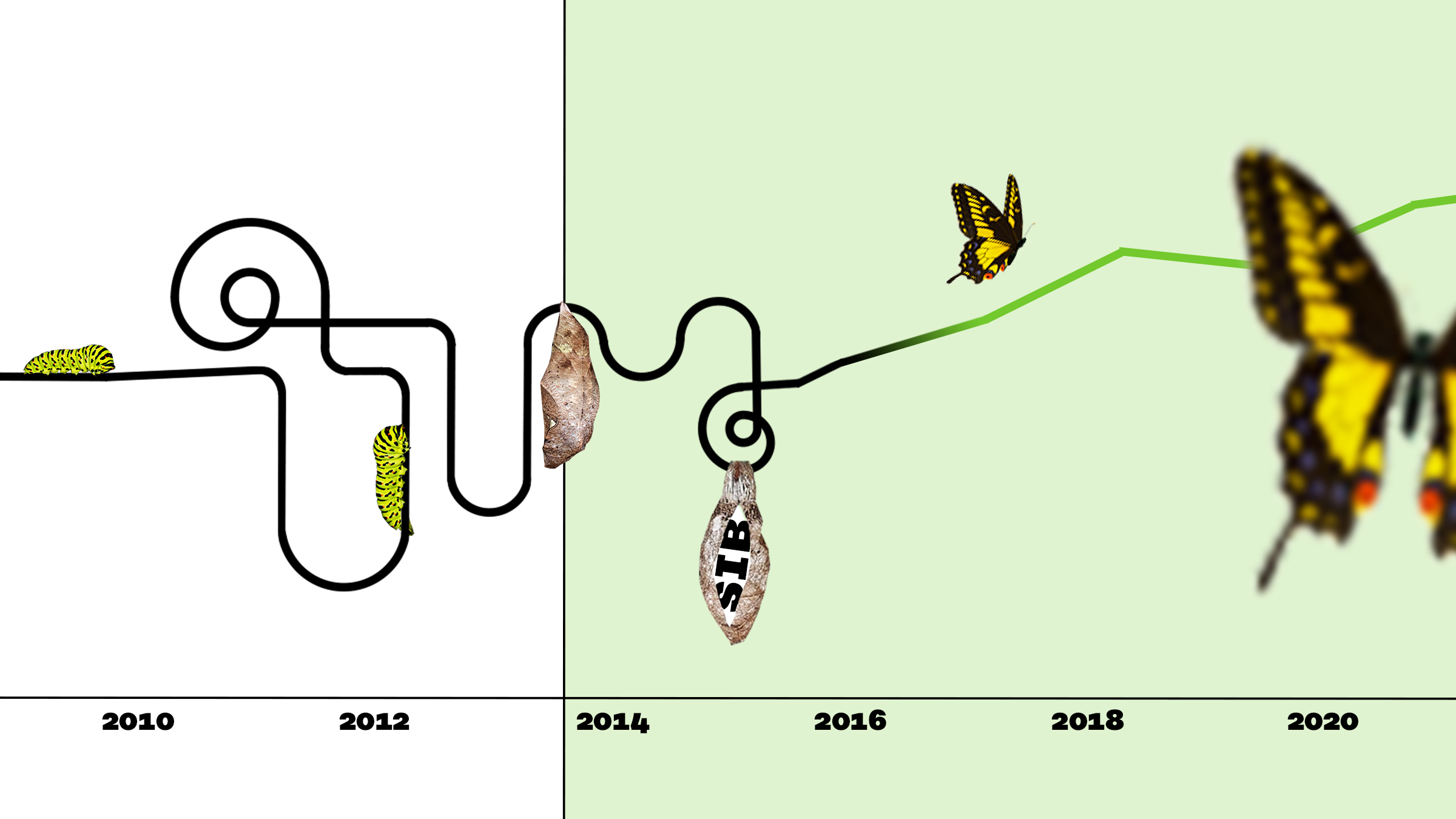

These are some of the questions that impact investing, launched at Sitra’s initiative, has been seeking to answer. In the space of five years, a total of seven SIB projects have been launched or are about to begin. They teach new lessons and lay the foundations for the enhancement of impact-oriented thinking and business intelligence in the public sector.

Impact investing is a broad term, and it encompasses many different methods of implementation. Sitra has focused particularly on one method of outcomes-based contracting, the social impact bond (SIB) model, in which the project is always owned by the public sector.

The SIB model was selected as the implementation method for impact investing because Finland has an extensive public sector. In this way, the benefits of impact investing – the savings made by society – will be reaped by the taxpayers. There are also other impact investing methods besides the SIB model that can be applied to steering outcomes-based activities in the public sector.

Inspiring opportunities – but many things slowing down the process

The idea of impact investing was relatively new when in 2014 Sitra decided to launch the impact investing focus area. International investors and Sitra had become acquainted with the subject a few years earlier through a study conducted by the Rockefeller Foundation. The new way of doing things got people talking in many other arenas as well, including the European Social Forum.

Impact thinking was a subject that awoke the interest of local authorities, organisations and investors alike. At the same time, it was known that there was still a lot to be learned about the competence needed to make the required impact, the data required for it and the entire operating method.

For example, local governments and different service providers believed that impact investing would be a good way of learning how to build effective services.

The expectations were high when projects were being planned. Even some Sitra employees thought that the SIB model could be a scalable standard tool that could be used for significantly speeding up the development of effective operations in different municipalities.

However, it turned out that each project needed to be built from its own specific starting point, and the SIB model could not be directly duplicated. At least at the pilot stage, each project has required separate implementation of the modelling, for example, because the project owners, such as local governments, have different needs and services.

It also transpired that the time required between the planning of projects and their launch was longer than originally estimated. Of course, from very early on it was obvious that it would take time to build the projects during the trial phase because of the large number of different organisations involved and the demanding nature of the problems to be solved. Furthermore, addressing the root causes of the various issues by means of modelling requires a lot of work.

However, the work carried out in the modelling of SIB projects made it possible to build clearer starting points for the implementation of preventive and proactive work in municipalities and to establish an overall picture of it. Modelling helps tackle the root causes of problems by means of actions that have proved effective.

The modelling of projects has provided local governments and service providers with valuable new information about services and gaps in service chains. In addition, the modelling process has shown whether the data collected by a local government on its services is sufficiently comprehensive and of high enough quality to serve as a basis for impact evaluation.

It has required a lot of work to find the information needed for the modelling from information systems. For example, for the modelling of the Children SIB project, some of the data had to be collected manually from the systems by employees.

Different worlds meet

At times, the encounters between different worlds in SIB projects have been challenging, but, at the same time, the different stakeholders have learned a lot from each other. A strong common goal has helped to build co-operation.

In SIB projects, the money comes from investors, but there has also been some mistrust of investors in the public sector, with people suspecting that the models are constructed in a way that makes it too easy for the investors to obtain their share of the financial results. On the other hand, some investors have criticised the returns on the models as being too low in relation to the risks involved when using a completely new type of investment method.

Many investors have also been unfamiliar with the public sector and its activities, and the entire SIB model has been new to them. Getting to know the world of SIB projects has required a lot of work from investors. They have also harboured preconceived prejudices about the new investment model, because, so far, there has only been limited experience of its results.

In some SIB projects, it has taken a long time before local authorities have decided to join the project, for many reasons. For some local governments, project-related decisions may be made on several levels of the organisation, for example by various committees. Occasionally, it has also taken time to obtain a joint decision from a group of investors. Even though there have been delays in decision-making and, therefore, in getting projects launched, the discussions with many different decision-makers have provided more information on impact investing and the objectives of the projects.

It has not always been easy to adapt a new kind of SIB model to the practices of local governments. For example, one of the practical problems encountered by local authorities has been how to account for the SIB project in the annual municipal budget. Local authorities have had to work out how they should pay the performance bonuses owed to service providers over a period of several years, for instance. Adopting the idea of an entirely new operating model has also taken time.

Current societal issues guide the choices

Despite the various delays inevitably related to learning new things, a total of seven SIB projects have been launched in five years.

The ongoing SIB projects and the ones under preparation are closely linked to recent societal issues. The first SIB project, the Occupational well-being SIB, was launched in 2015. Already back then, there was a lot of talk about extending working careers and coping at work. The number of working-age Finns retiring prematurely was so high that it was already becoming a threat to the national economy.

In a background study for the SIB project, Sitra examined how premature retirement could be reduced. The study showed that the development of occupational well-being in the public sector in particular appeared to be of essential importance, as the number of sickness absences was approximately twice as high in the public sector as in the private sector. The costs of these absences are also directly borne by taxpayers.

For Sitra, the was the first concrete way of presenting to local authorities, ministries, organisations and investors a way of thinking and operating that at that point was still unknown in Finland. The project also provided Sitra with feedback on its plans.

The meetings with municipal office holders led to the discovery of new needs that could be solved by impact investing.

Although local authorities considered well-being at work an interesting topic, they told Sitra in several meetings that they had even bigger and more pressing issues on their desks. As examples, they mentioned the social malaise experienced by families because of unemployment and the costs of child welfare measures. This feedback and new studies were to steer the selection of the next SIB projects.

Up to 20 million euros saved by the Integration SIB

Finland’s second SIB project was launched in 2017 and, at the time, it addressed a very topical social challenge. In 2015 and 2016, many more asylum seekers arrived in Finland than in previous years, and new ways of integrating and employing immigrants were needed. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment hoped that Sitra would help them build a new SIB fund related to this theme. This is how the came into being.

The difference between the Integration SIB and the traditional integration and employment of immigrants is that the service providers involved in the project are paid for the results they achieve and not just for the number of training days they provide, for example.

By August 2019, nearly 2,000 immigrants had participated in the Integration SIB programme, and almost 750 of them had found employment through the support received. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment estimates that the Integration SIB has generated savings for the government of as much as 20 million euros.

The third SIB project, the Children SIB, created to promote the well-being of children, families with children and young people, also tackled a major social challenge.

When the project was being built, particular attention was paid to the reasons why families become child welfare service clients. The analysis showed that families with children who had neuropsychiatric symptoms or diagnoses were at a higher risk of needing substantial provision of child welfare services.

The problems these families have do not fit into the siloed way of treating situations in society, where each sector is only responsible for its own activities. These families need support from across the board, from healthcare, social services and schools, and too often assistance is not available early enough. Therefore, the objective of the SIB project is to increase the capacity to help families in a more comprehensive and effective manner.

Within local government, the Children SIB project in particular sparked a lot of debate about the morality of the model providing investors with an opportunity to earn at the expense of the most vulnerable people in society, and about what the roles of local authorities and investors should be.

Like the Children SIB project, the Employment SIB was also created on the basis of discussions with local authorities. The reasons behind it were the intergenerational challenges and the accumulation of problems generated by unemployment and social exclusion.

The preparation of the Employment SIB partly took a new direction when Prime Minister Juha Sipilä’s government decided in its mid-term session in 2017 to use it as one of the means of supporting the employment of young people. The responsibility for running the project was assigned to the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, although since the Employment SIB was launched at the end of 2019, there have yet to be any results produced on the project.

Environmental themes as SIB projects

The reform of the social welfare and healthcare system, or rather the delay of the process, has also affected the preparation of SIB projects. The launch of a project focusing on the prevention of type 2 diabetes has been postponed, because the payer of the potential performance bonus changed during the preparation process.

At first, the bonus was supposed to be paid by local authorities, then by the regions in accordance with the social welfare and healthcare system reform, and now, again, by the local authorities. The same challenge was also encountered in the preparation of the Age SIB, one of the key projects on ageing of Juha Sipilä’s government.

The increasing interest in the climate theme and energy efficiency is also visible in the topics of SIB projects. At present, there are two environmental funds under preparation, one under the Ministry of the Environment and other under the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. These are among the first environmental SIB projects in the whole of Europe.

High expectations remain

It takes years before the final results of SIB projects become visible. For example, in the Children SIB one of the municipalities involved will get the results in 12 years’ time. Usually, the results can be expected within four to six years. In autumn 2019, the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health completed its evaluation of the Occupational well-being SIB, the first SIB project launched in the Nordic countries and Finland.

In all SIB projects, the participants continuously monitor how the impact and performance targets are being met. Based on the monitoring, the service providers will, if necessary, change the way they do things to ensure that they reach the impact and performance targets.

In fact, one of the major lessons to be learned from SIB projects is how it would be easier for local authorities to purchase results instead of the performance of tasks. SIB projects are one way of acquiring results. Even the existing procurement methods would allow purchasing results if only the public sector were to modify its way of making purchases, basing them on outcomes.

The results of SIB projects are still subject to high expectations. If the ongoing and planned projects are implemented as planned, Sitra estimates that they will save local authorities and the state about 170 million euros by 2030.

Project Director Mika Pyykkö and Leading Specialist Anna Tonteri from Sitra were interviewed for the article.

Sitra’s work on impact investing will be continued by the Centre of Expertise for Impact Investing, which began its operation under the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment at the beginning of 2020.

Recommended

Have some more.