This series of articles – Sitra Trends – reviews the trends listed by Sitra during October 2014, from a variety of perspectives.

We have already exceeded the biocapacity of the Earth in many respects and are under increasing pressure to achieve sustainability. The pressure to attain sustainable consumption is growing as resources become scarcer and prices rise.

We have entered a symbolic year with regard to global sustainability. The United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals have been extended into 2015, and the UN is currently preparing new Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. A United Nations summit is being held between 25 and 27 September 2015 in New York to decide on new global development goals. Although attempts to colonise other celestial bodies are increasing (SpaceX, Mars One, Boeing, NASA), the future of humankind’s peaceful coexistence on this planet is largely tied to finding sustainable solutions to environmental challenges.

Sitra’s leading advisor, Jukka Noponen, stresses the urgency of the situation: “If we’re not ready for a change of direction in the autumn, the world will plunge deeper into crisis. Conflicts and terrorism are becoming more commonplace, and this is not unconnected to environmental issues. We cannot keep delaying decisions until the next summit.”

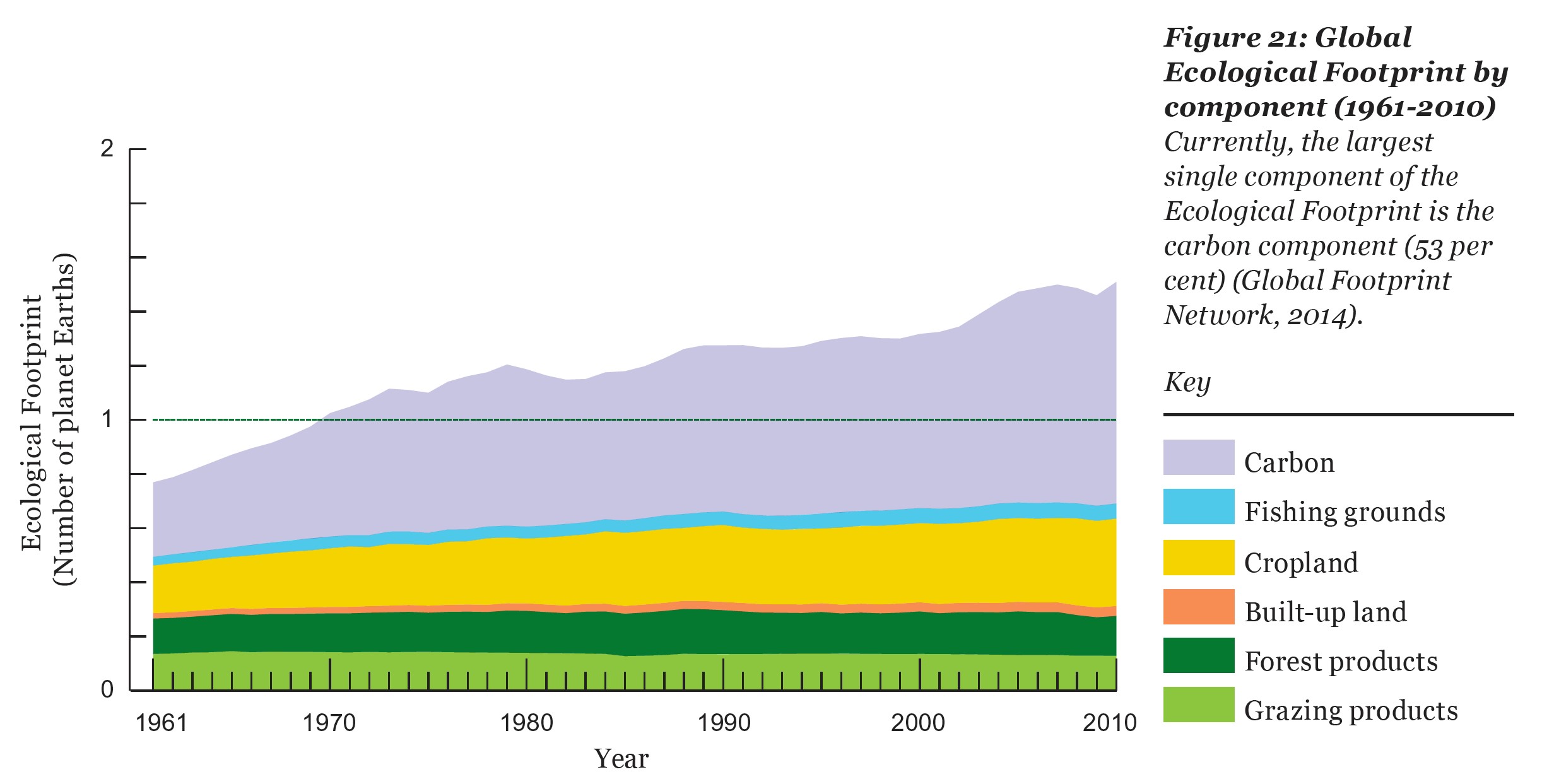

Last year, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) published the Living Planet Report 2014, which drew attention to our central – and vital – global environmental challenges. This publication includes the Global Footprint Network’s analysis of countries’ ecological footprints. Our global ecological footprint increased from 7.6 billion global hectares (gha) to 18.1 billion global hectares between 1961 and 2010. On the other hand, the world’s loading capacity also increased during this period from 9.9 billion global hectares to 12 billion global hectares. Since the 1970s, we have been consuming our Earth’s ecological reserves.

The situation will only get worse as the world’s population grows. According to the UN’s median-variant projection, the global population will rise from its current 7 billion to 8.4 billion people in 2030 and 9.6 billion in 2050. If current trends continue, growth in the Earth’s biocapacity will not catch up with our growing footprint.

Figure 1: WWF Living Planet Report 2014 (Source: Global Footprint Network, 2014)

At the national level, we can see that the ecological footprints of Western countries and the Middle East’s oil-producing nations are many times those of emerging countries. As poorer countries quite rightly become wealthier, we will most likely find ourselves under even greater ecological pressure. The majority of our global footprint consists of our carbon footprint, as we seek to satisfy our growing hunger for energy.

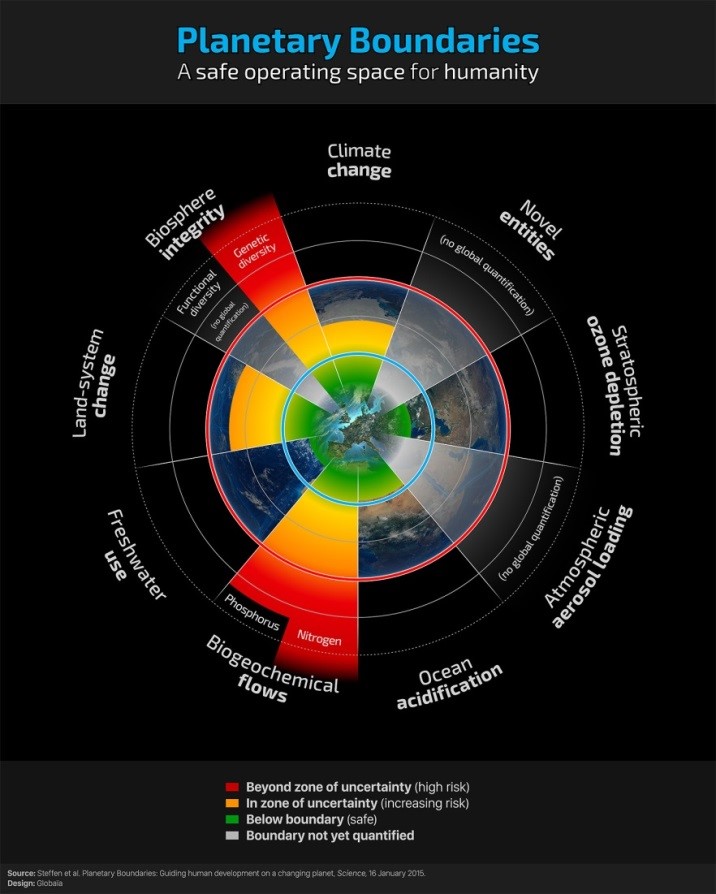

Although our carbon footprint is responsible for climate change, climate change is not our only alarming environmental problem. In January, the Stockholm Resilience Centre published an updated research report on the limits of the Earth’s loading capacity in the journal Science: Planetary Boundaries 2.0 (Steffen et al., 16 January 2015, Science). According to this research report, the Earth’s loading capacity has already been exceeded in four areas: biogeochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorus), biosphere integrity (genetic diversity), land-system change (land use), and climate change. The deterioration in genetic diversity and the exceeded loading capacity for nitrogen and phosphorus are particularly alarming.

Figure 2: Planetary Boundaries 2.0 (Source: Stockholm Resilience Centre, 2015)

Industrial and agricultural fertilisers contain nitrogen and phosphorus that leak into water systems, causing eutrophication and suffocating marine life. Finns have cause for concern very close to home, as blue-green algae and thread algae have increased dramatically in the Baltic Sea over the past few decades. Combined with overfishing, eutrophication has driven marine species to extinction or near-extinction all across the world.

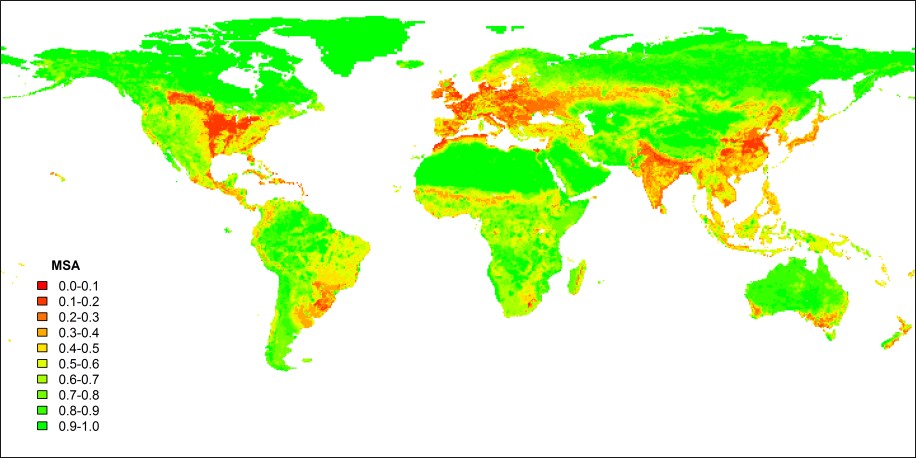

Genetic diversity in the natural world has long been deteriorating. The WWF estimates that between 1970 and 2010, vertebrate populations fell to half the number 40 years ago (WWF LPI). According to a study published last year, the extinction rate of species is currently thought to be 1,000 times greater than in the era before humans, although the figure may be even higher. The Stockholm Resilience Centre has also mapped the global disappearance of species.

Figure 3: Changes in terrestrial mean species abundance (MSA) (Source: Stockholm Resilience Centre, 2015)

There has been a great loss of biodiversity in areas inhabited and cultivated by humans. In the United States, Europe, India, China, south-east Brazil and south-east Australia, the mean species abundance (MSA) indexes for native organisms have fallen below 0.2 over vast areas. The monocultures arising from intensive agriculture and forestry have replaced natural habitats all across the globe.

There is no shortage of challenges. But are there any positive trends to be seen?

In the future, the human race must be able to disconnect improvements in well-being from environmental loading. A circular economy based on closed loops has been suggested as a way to maximise the value produced from natural resources while minimising environmental loading. Increasing well-being with a smaller carbon footprint also makes sense commercially, through savings and new business models. By monitoring companies’ value networks at system level, the nitrogen and phosphorus used in industry and agriculture would not escape into water systems either.

At Sitra’s circular economy seminar in January 2015, the idea of shifting to a circular economy in Finland gained support among all parties. In March, Sitra will be launching a new key area to support Finland’s shift to a circular economy by establishing a common desire to adopt a circular economy, and by creating and piloting circular economy business models that support environmental management.

New solutions have also been raised for another of our alarming problems. Habitat banks have been suggested as a means of retaining biodiversity. This topic has been discussed in Finland and at the EU. Business operations that reduce and threaten biodiversity would be obliged to pay compensation for lost biodiversity to a third party whose own operations would increase biodiversity elsewhere.

As our society gains an increasing awareness of the value of ecosystem services and diversity in areas such as our health and mental well-being, the purely commercial profitability of habitat banks will also increase. However, in order to remove any barriers to the success of habitat banks, it is important to co-ordinate co-operation between the private, public and third sectors. If our shoes won’t stretch, maybe changing our position will make them pinch a little less.

Links:

Sustainable development goals

Sustainable Development Goals: Working Group proposal

The growing middle class

It’s worth spending time in the forest as a child – it may even reduce sensitivity to allergies (in Finnish)

Estimating the Normal Background Rate of Species Extinction

Previously published in this series:

Skills will challenge information

Stable employment becoming a thing of the past

Europe’s structures are crumbling

The effects of climate change are spreading outwards

Well-being to rise in importance

Recommended