I had the privilege of working for almost two days with top-level experts from European think tanks on ways to envisage the future of Europe as a pioneer of the fair data economy.

In a fair data economy, individuals decide on the use of their data and organisations that want to provide services to individuals must use data in a fair and transparent way. A fair data economy benefits everyone. “Treat humans as actors, not as a production factors” was one of the conclusions from the Vision Europe Dialogue 2019 event on 1 and 2 April 2019 in Helsinki, Finland.

Ahead of the event, Vision Europe’s partners provided short articles on a variety of topics including the policy on the digital economy in the EU, the technological change in democratic disruption, and vision for philanthropist data economy. In an attempt to make digitisation very real, discussions centred on our future digital lives and on the future of work, in addition to a demand for the education of what we may call digital visionaries.

The wide range of topics covered by these atricles presumably highlights the complexity of the data economy and the lack of a definition of “fairness”. Often, complex topics turn into debates. To avoid that, a new dialogue-based concept was introduced, in the hope that these leading experts might find new ways to introduce abstract topics like the data economy into the public debate and make them more understandable ahead of the forthcoming European parliamentary elections.

This article reflects these insightful dialogues and key note speeches and gives an (subjective) overview on the key topics discussed in Vision Europe Dialogue 2019.

Collaboration between US and EU – “the art of the deal” meets “the art of compromise”?

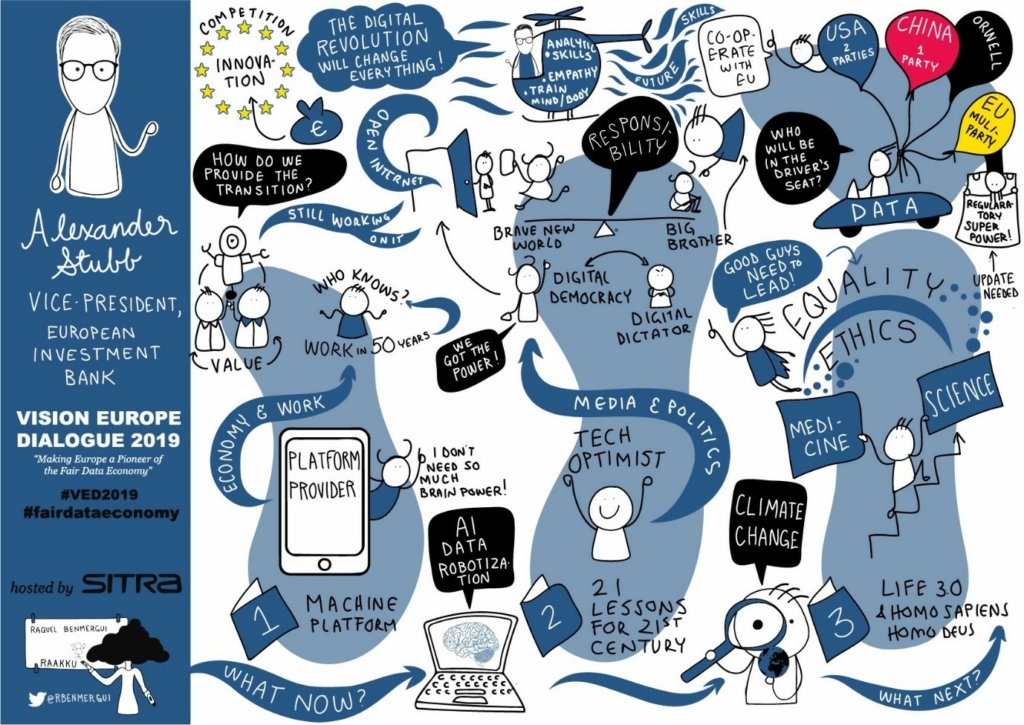

The event was opened by Alexander Stubb, the former Prime Minister of Finland and currently Vice-President of the European Investment Bank. He highlighted three essential elements of the digital revolution: 1. its effects on the economy and future work; 2. its influence on politics and the media; and 3. the impact on science and the future of mankind.

No matter how you see technology you will have to cope with huge challenges in the future; climate change is an undeniable challenge. The use of technology and the combination of AI and data, together with robotisation, will change our future. “The rise of the useless class” (a term coined by Professor Yuval Noah Harari) might be inevitable as a result of AI and robotisation, but we have the capabilities to shape that inevitable future into more a sustainable future.

Creativity, not just skills in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), is needed for facing future challenges. While AI is changing the way medical doctors and lawyers work, these vocations will not disappear; instead it will simply be the way of working that changes. Empathy is an ability that will be necessary in the future and if it is not maintained and trained the feeling of togetherness will be lost from our societies.

Co-operation, regulation, innovations, best practices and ethics are needed in the digital revolution.

Asia, the US and the European Union have taken very different approaches to data privacy and people’s rights on the use of personal data. Instead of condemning alternative approaches, perhaps the EU, as a “regulatory superpower”, could seek to ally itself with US. Although it may seem that the US is polarised at the moment there are shared values between the US and the EU. California’s Consumer Privacy Act, which is similar to the EU’s GDPR, perhaps shows that Europe could lead the way when it comes to a fair and human-centric data economy in general. The US excels in “the art of the deal”, while the EU is built upon the “art of compromise” – perhaps the two can find mutual benefits from collaboration?

In his conclusion, Alex Stubb highlighted five opportunities for Europe to survive the digital revolution.

- Europe to actively co-operate with the US.

- Continued work on competition law (anti-trust against big tech).

- A continued and strengthened focus on innovations (EIB – European Investment Bank being an essential element here).

- The opportunity to gather best practices and frameworks to update the regulations on privacy (GDPR).

- A focus on Ethics and AI (“AI is as big as biological warfare; it needs to be handled with care”).

Data Economy Scenarios – to change direction we need a deeper understanding

The first dialogue session focused on different scenarios for the data economy. For the purpose of the dialogue, existing data economy models were explained and defined as four different models: big brother, broken, siloed and fair.

From the dialogue’s conclusions, it became evident that Europe will slip from a siloed model to a broken model if measures are not taken to change direction. Changing direction demands not only an understanding of different political and regulatory drivers, but also an understanding of the diversity among different European countries.

A common conclusion from the first dialogue’s discussions was that more work at a more granular level is needed in order to create a framework and clear definitions for different scenarios.

Understanding diversity and creating hybrid models is the key to defining a European way for the data economy.

Making technology more human and understandable

For policymakers, an omnipresent theme is the existence of both threats and opportunities from Artificial Intelligence (AI). Algorithms are embedded in digital services and thus affect our everyday lives and shape the future of our digital lives.

Nonetheless, based on a recent survey by Bertelsmann Stiftung, 48% of Europeans do not know what an algorithm is. Based on the same survey, 74% want more rigorous controls on the use of algorithms, 46% see more advantages and 20% expect more problems (Discussion paper Ethics of Algorithms #10 Results from a representative survey What Europe knows and thinks about algorithms). A relevant question for all policymakers and researchers is: how can we make technology more human and understandable, and more relevant to our everyday lives?

48% of Europeans do not know what an algorithm is.

What is essential for the success of a European digital economy is building a modest but targeted strategy on 1) how to speed up development of big data and AI and to help companies to pool the data they need, 2) how to use GDPR to empower individuals in the face of the technology giants so that individuals have more control over their data and its accessibility, 3) to ensure interoperability and reduce the ease with which companies can “lock in” users and 4) to combine ecological sustainability with digital sustainability. Economic reasons dictate that there must be a sense of urgency to all of this, since EU regulations are being caught up by others, and we risk losing the momentum we have gained as a regulatory superpower.

What will be good work in the future, and is there a role for data as a professional asset?

Good work might be defined as having access to work, flexibility, protection and personal growth. One participant reminded us that “work” is a verb, not only a noun, so perhaps an employee’s ultimate power is the ability to step in and out of labour markets. Engaging people and encouraging them to partake in lifelong learning in order to keep their skills up to date are vital for a sustainable future working life.

Redefining work, and ensuring social security, has important implications for employment, education and welfare. Stability is created by ensuring individuals have the right skill sets for the future; it is no longer created by employment contracts alone. To talk about a “non-traditional workforce” will lead us in the wrong direction, since the characteristics for our working life are constantly evolving. Technology has affected engineering in many ways, and engineers have lost their jobs many times, but there is still a shortage of engineers. The key to success is to learn how to train and motivate people to work.

Platform workers form a small but increasingly important group within the European workforce. In defining the direction for future work, it is important to understand the nature of platform workers, since their status in the labour market is currently frequently unclear. On the other hand, platforms bring flexibility to markets so that even people with lower skills can be part of the workforce.

It is inevitable that the volume and characteristics of work will change.

Digital platforms can also be seen as co-creating platforms, where platforms and workers benefit from new opportunities not available in traditional structures. In future we could have digital CV’s, so that we could more easily quantify our skills and negotiate for compensation. Perhaps when data is used as a professional asset, there will be better mobility and transition capabilities even for platform workers. In addition, for flexibility, perhaps both traditional workers (and systems) and platform workers can learn from each other?

It is inevitable that the volume and characteristics of work will change. Some researchers have estimated that almost 50% of jobs will disappear as a result of technology, AI and digitisation, but current estimates suggest that this is a wild exaggeration and that the reality is that closer to 10% of positions will disappear. Still, the increasing number of platform workers and the increase in those who are self-employed raises questions about how to secure pensions and social security. What need will there be for social protection in the future, and how do we ensure that social contracts are relevant even to the younger generations?

Data as a common good?

It was concluded that it is very important to continue discussions on the data economy and its many different aspects. We should not just discuss economics, but perhaps introduce a concept of a “philanthropic data economy”. We need to have a broad scope so that we can be sure not to ignore some people, phenomena or issues. Also, we should see the strengths, like open data and reserves of public data, as important building blocks towards a fair data economy.

It was concluded that data should be available for everyone and reusable by anyone. Different aspects of data were also discussed, and, once again, raw data was compared to oil. From this followed a discussion on how the earnings from the raw material, data, should perhaps be returned to society.

Data should be seen as a common good, benefiting societies and individuals.

An interesting example is the Norwegian Government Pension Fund (also known as the Oil Fund). It was established in 1990 to invest the surplus revenues from the Norwegian petroleum sector. In May 2018 it was worth about 195,000 US dollars per Norwegian citizen. The fund holds real-estate portfolios and fixed-income investments, but many companies are excluded by the fund on ethical grounds. Perhaps a similar system could be built for fair data usage, ensuring the responsible use of data and returning a share of the earnings from public data back to society?

Europe is built on lawful, ethical and robust foundations – the world’s smartest lawyers should be building vertical solutions

The second keynote speech at the Vision Europe Dialogue event was presented by Pekka Ala-Pietilä, chair of the EU’s High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence. He started his presentation by reminding that, with Artificial Intelligence, we are on an exciting journey, a journey that will bring both positive and negative insights. Even the most advanced platform-based corporations are now merging old structures with new innovations as part of their business models – the digital economy is a hybrid of the old and the new.

For Europe to succeed in the digital economy we need to build strong horizontal foundations that are lawful, ethical and robust. On top of that, vertical application areas for industry-specific needs need to be assessed. Requirements for regulation and practical implementation vary depending on whether we are talking business-to-consumer, business-to-business or public-to-citizen domains. Each domain is different, so the skills needed to benefit from AI and operate in different verticals are very different.

Our common goal could be to maintain Europe’s position as a regulatory superpower.

In his speech Pekka Ala-Pietilä challenged us to consider whether “having the smartest regulators in the world” should be a common goal for Europe in order to maintain Europe’s position as a regulatory superpower. Perhaps Europe could take a lead in educating the smartest regulators, understanding and applying ethical AI in different domains and thus ensuring that the GDPR can enable the sustainable use of AI and lead to the construction of a fair and human-driven data economy.

We were lucky with the GDPR; recent data breeches and increasing issues with privacy have demonstrated the importance of solid regulation. On implementation of regulation, early best practices are available, like the new legislation on secondary use of healthcare and social care data in Finland. These vertical solutions clarify the practical implications of GDPR for research, development and innovation.

Technology is changing fast. Velocity, variety and volume, the characteristics of big data, are changing. The direction might also be towards small data, or almost practically no data, since rule-based decision-making needs no data. While still in its early days, one interesting example is that from AlphaGo Zero on how the specialist systems that leverage enormous amounts of human expertise and data are perhaps just an interim phase in the development of AI. The attempt is there, creating algorithms that achieve superhuman performance in the most challenging domains with no human input. This pinpoints the importance of ethics and common ethical guidelines.

What are the characteristics of a fair data economy?

Data should be seen as a common good. The GDPR and common privacy regulations define the boundaries of data usage. It should be ensured that there are no data monopolies outside of our control. We need to set common, human-centric rules, so that there is trust that the common good is not misused. Governance processes need to be developed.

In addition to the rules and regulations, the work needs to be continued. Enforcing the GDPR means driving the free flow of data and innovating to create new uses for data. At the same time, there is a need for algorithmic impact assessments and public-sector benchmarking. Perhaps there should be common trust marks for consumers to identify services built on a fair and ethical base, respecting the rights provided for by the GDPR? Further work on standards and perhaps a common code of conduct for the data economy is needed, or perhaps the direction should be towards defining personal terms and conditions’ is there a need for defining “My terms” instead of the generic corporate-issued user terms when it comes to use of personal data?

How about defining My terms?

What are the characteristics of a fair data economy? Fair should mean that the economic model is fair for people. It becomes fair when a well-functioning economy is combined with a feeling of purpose of humans. Humans should be treated as actors, not as production factors. Ensuring social inclusion is crucial in a data economy. There need to be ethical data-management services for consumers. Perhaps there could be transparent databanks or governmental transparency services ensuring trust and inclusion in society? In the data economy, who is has the role of watchdog when it comes to setting guidelines, training and safeguarding data usage?

There is a need to share best practices for solving issues across the EU, and innovative models could perhaps be modelled on the best cases from other sectors – perhaps there is a need for data unions similar to trade unions in order to ensure any evolving economic model is fair and equal for all? Sustainable business models are possible. They are based on data and there have been positive developments, but in order to be optimised, there must be measurement frameworks for the data economy and for the impacts of data on economies. Ideal visions are easy to create, but the challenges lie in their execution. As a consequence, there must be provision for the future.

Lifelong learning demands smart and simple communications, peer learning, and inspirational and easy-to-access solutions for educating people. Skills and jobs, and quantified CVs in digital form that lead to the increased mobility of the workforce will be important in the future. Awareness and an overall level of understanding of the implications of the data economy should be widely promoted; perhaps a consortium of think tanks has a role to play?

Sitra is working on a roadmap together with Lisbon Council to make this happen. The discussion paper will be published soon. Preorder now!

#VED2019 #fairdataeconomy #IHAN

Articles

Read more