Sitra’s new international study, “1.5-degree lifestyles – Targets and options for reducing lifestyle carbon footprints”, proposes clear targets and alternatives for cutting the emissions caused by our consumption. The change required is radical: the current per capita carbon footprint in Finland must be reduced by up to 93% by 2050.

The carbon footprint of households and individuals’ lifestyles – in other words what we buy and eat, where and how we live, how and where we travel – lays a foundation for the emission reduction measures. Changing our lifestyles could indeed have a visible and fast impact on reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

The study proposes global carbon footprint targets and options that will help society make lifestyle changes to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees at the most, as specified in the Paris Agreement. The literature dealing with the subject, political decision-making and business life have all so far focused mainly on the carbon footprints of certain countries, cities, organisations or products, but not on that of consumers.

This has partly weakened the efforts to solve the climate crisis. The discussion on solutions to climate change has been largely related to technologies although systemic changes concerning people’s behaviour and the infrastructure also play an important role.

The gap between carbon footprints and the targets

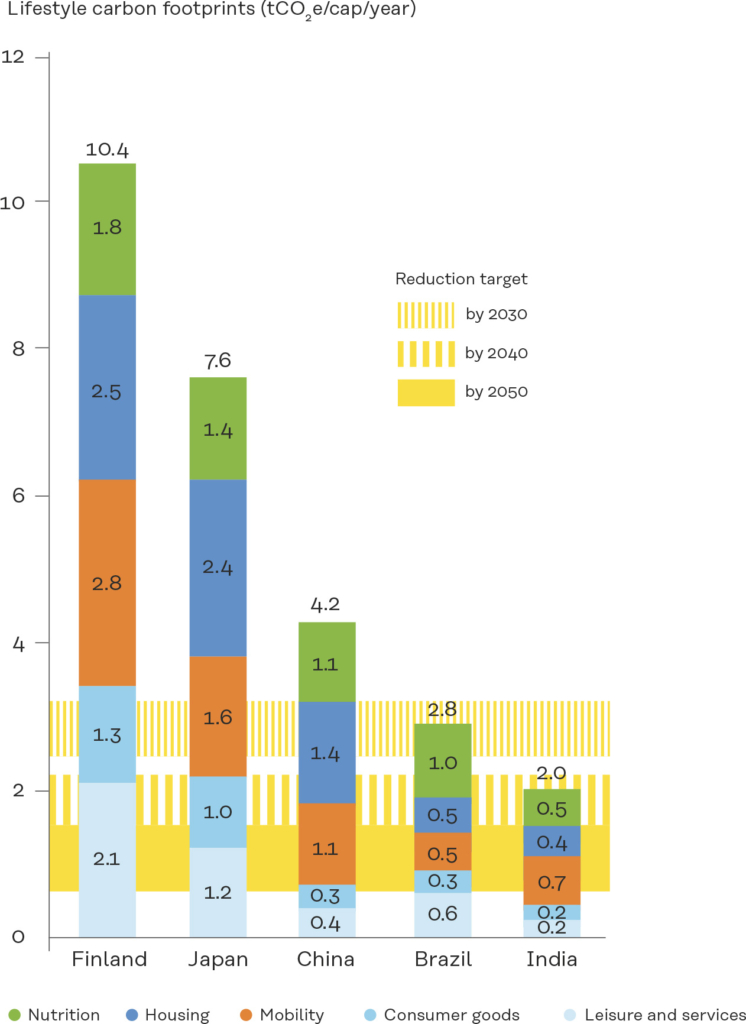

The results of the study highlight a huge gap between the current average per capita carbon footprints and the climate targets. In 2017, the average annual lifestyle carbon footprint per person in the countries subject to the study was 10.4 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents (tCO2e) in Finland, 7.6 tonnes in Japan, 4.3 tonnes in China, 2.8 tonnes in Brazil and 2.0 tonnes in India.

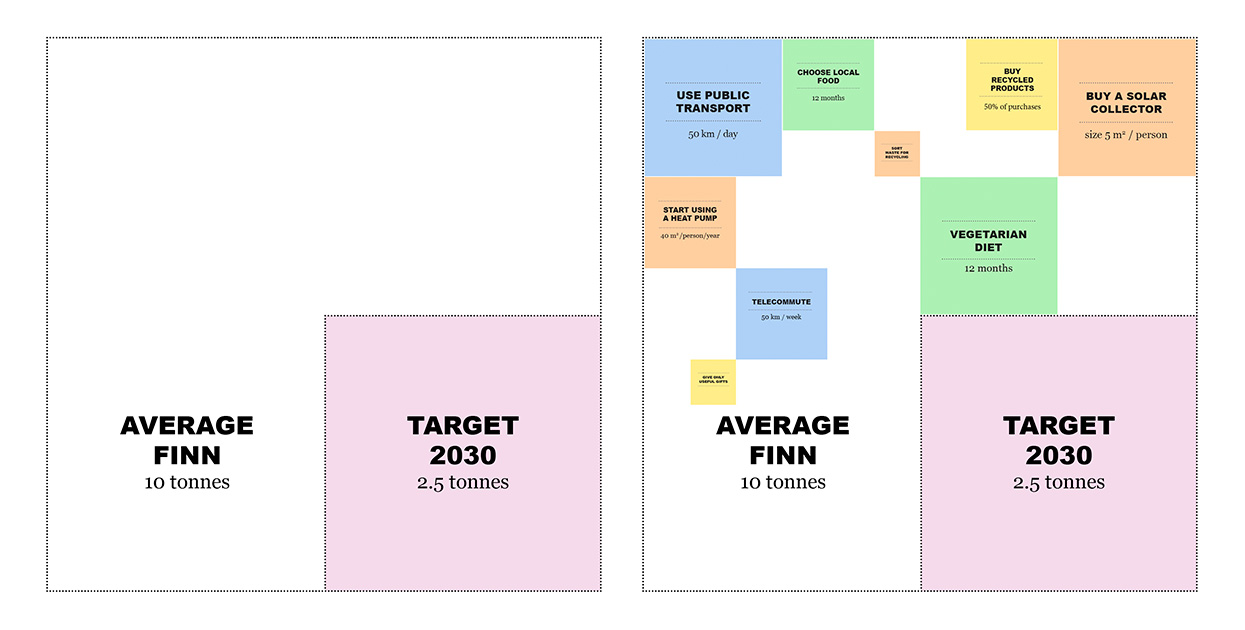

Based on the emission reduction scenarios, the study proposes that the target level for the carbon footprint of consumption per person should be 2.5 tonnes of CO2e by 2030, 1.4 tonnes by 2040 and 0.7 tonnes by 2050.

The slower we reduce emissions now, the more and faster we will have to reduce them in the future.

These targets are in line with the 1.5-degree target of the Paris Agreement, enabling us to stop the global growth of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible and ensuring that we will rely as little as possible in the future on negative-emission technologies, in other words, technologies that bind carbon dioxide back to the soil to reduce emissions.

The wealthy Western countries in this study – Japan and Finland – will have to reduce current lifestyle carbon footprints by as much as 80 to 93% by 2050, assuming that the measures to achieve reductions of 58 to 76% are taken immediately to reach the 2030 target. The developing countries in the study – India, Brazil and China – will also have to reduce their carbon footprint by between 23 and 84% by 2050, depending on the country and the scenario.

The report looks at greenhouse gas emissions and the potential to reduce them from the perspective of consumption and lifestyles. The lifestyle carbon footprints have been defined as greenhouse gas emissions directly emitted and indirectly induced from household consumption, excluding the emissions induced by government consumption and capital formation, such as infrastructure.

In its special report, “Global Warming of 1.5 °C”, the Intergovernmental Climate Change Panel IPCC emphasised the need for rapid changes to enable significant cuts in greenhouse gas emissions. The significant impact of our behaviour, lifestyles and consumption habits on climate change has been recognised.

Changing our lifestyle could therefore have a visible and fast impact on the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions in those areas of consumption that are not locked into the existing infrastructure. For example, it is easier for individuals to reduce the emissions caused by their diet at any time by making new types of purchase decisions, whereas the city structure and road infrastructure that have been designed for driving may make low-carbon transport alternatives slow or difficult to implement.

What makes up our lifestyle carbon footprint?

About 75 per cent of the lifestyle carbon footprint calculated on the basis of average consumption consists of food, housing and transport. A closer inspection reveals that there are several hotspots causing a great deal of emissions. These are the consumption of meat and dairy products, fossil fuel-based energy consumption of households, private use of cars and air travel.

Some of the hotspots, such as car use and the consumption of meat products, are found in all of the studied countries while some of them are country-specific, such as the consumption of dairy products in Finland and the electricity based on fossil fuels in Japan. This shows that the local situation must be taken into account and tailored solutions must be sought when efforts are made to reduce the lifestyle carbon footprint.

Low-carbon options that reduce the carbon footprint

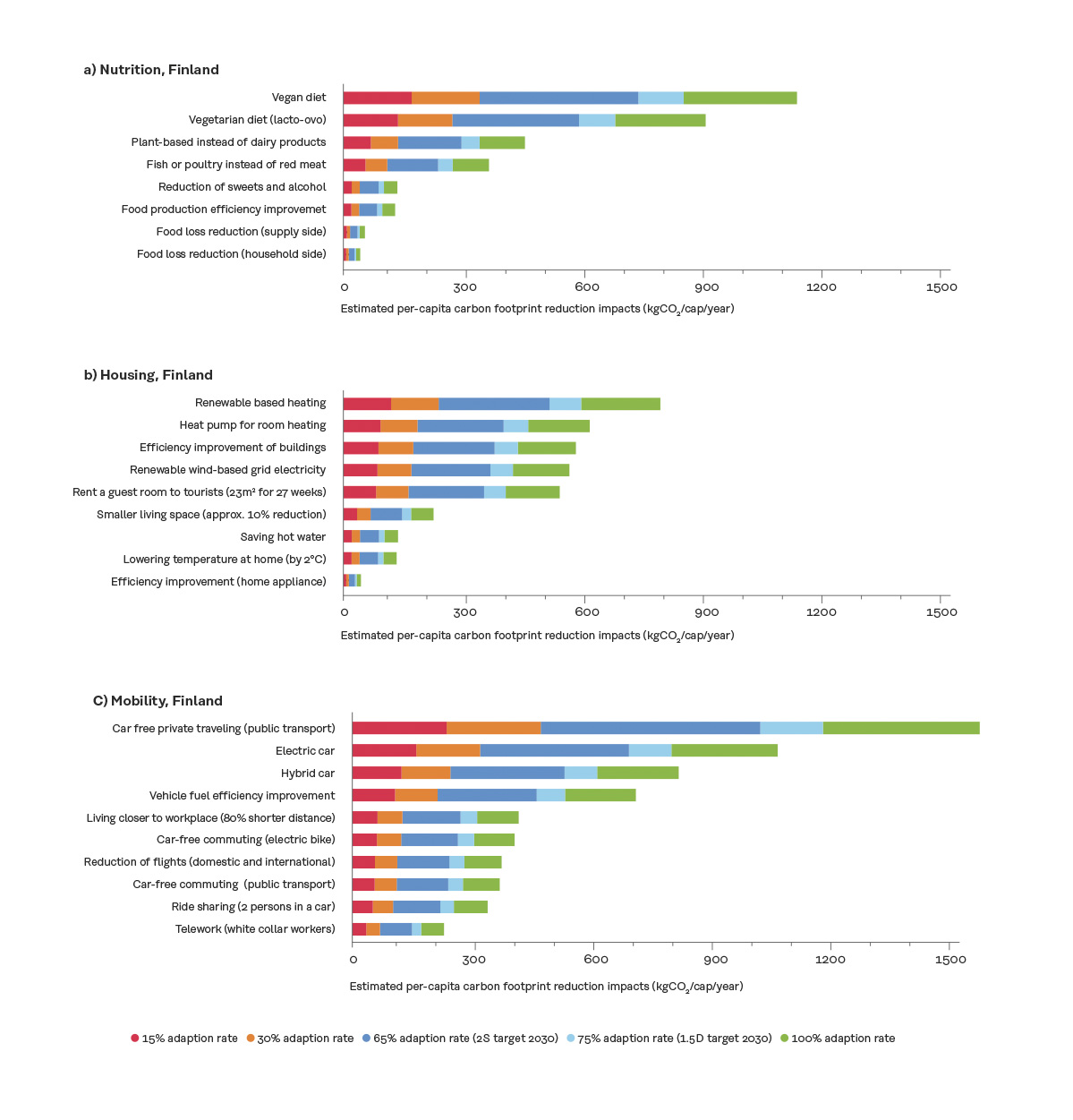

According to the study, the options that have the greatest potential to reduce carbon footprints are the following: replacing car use with public transport or electric bikes when travelling to work or during free time; introducing electric and hybrid cars; improving the fuel efficiency of vehicles; increasing carpooling; living closer to one’s workplace or place of study; moving to a smaller living space; producing electricity and heating from renewable energy sources; using ground-source and air-source heat pumps; favouring a vegetarian/vegan diet; replacing dairy products with plant-based alternatives; and replacing red meat with chicken or fish.

The three main approaches for reducing the carbon footprint are absolute reduction, efficiency improvement and modal shift, in other words, moving from one mode of consumption to a lower-carbon one, such as changing from driving to using public transport, changing to a diet rich in vegetables or replacing fossil energy with renewable electricity and heating energy.

The lifestyle options overlap partly and their impacts vary according to how extensively they are implemented. By fully implementing individual options, the carbon footprint calculated per person can at best be reduced by hundreds or even more than one thousand kilos (CO2e) per year.

With extensive lifestyle changes, we could significantly enhance the achievement of the 1.5-degree climate targets by 2030. However, this would require an extremely ambitious implementation of low-carbon alternatives, for example, in Finland and Japan. The 30 or so alternatives presented in the report should be implemented to the level of 75 per cent in society, by each individual or by a combination of these.

How do we achieve 1.5-degree lifestyles and who should take action?

This report is one of the first international reports proposing global target levels, calculated per person for lifestyle carbon footprints that are compatible with the 1.5-degree climate target. The report evaluates practical measures in the different areas of consumption. Politics, administration and companies should extensively support a transition to lower-carbon lifestyles.

Interactive tools such as the 1.5-degree lifestyles puzzle can help households as well as policymakers, administrations and companies identify problem areas related to reducing carbon footprints and develop solutions for them. To measure the feasibility and acceptability of low-carbon solutions, the solutions should be tested in households, residential areas and municipalities with active support from the public and private sectors. The methods and approaches presented in the report can also be implemented in other countries.

Implementing the recommendations of this report is an immense challenge. In addition to individual solutions, the implementation of the recommendations requires changes at the level of the entire production and consumption system. We must change the ways of thinking on which our economy, infrastructure and consumption-centred way of life are based. This requires a radical rethink in politics and administration as well as in business models and the lives of individuals.

Low-carbon options should not just be seen as restricting alternatives, but as new opportunities to improve business, employment and the quality of life.

The capacity of all operators to change should be improved in both industrial and developing countries. At the same time, the social acceptability of the changes should be ensured. Developing countries in particular should ensure that the basic needs of their populations are satisfied when carbon footprints become smaller. However, this challenge also offers opportunities for a better life and profitable business.

It goes without saying that these measures must be carried out urgently if we want to proceed towards a sustainable future and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees.

- Sitra’s study “1.5-degree lifestyles” is based on the technical report “1.5-degree lifestyles: Targets and options for reducing lifestyle carbon footprints”. The methods used in the study, the sources of information and the results of the evaluations are presented in detail in the technical report and its appendices.

Recommended

Have some more.