A large group of influential players from Finnish politics, business, industry and enterprise gathered in Helsinki in February to discuss whether environmental technology and services – the cleantech sector – could become the new driver and cornerstone of Finland’s economy. The debate proved that the key competitive assets are efficient use of energy and natural resources and low emissions from industrial processes – elements at the heart of the cleantech industry.

Participants also seemed to agree on the fact that global challenges involved in climate change and the scarcity of natural resources would result in a structural reform of production and industry. A low-carbon approach and a more efficient, even revolutionary, use of raw materials and energy would create new markets and opportunities for enterprises in a completely new way. In addition, Finland has experience and expertise that we must be able to capitalise on.

Some participants even mentioned a “new Nokia for Finland”, referring to reports placing Finland among the five leading cleantech nations in the world. Companies were encouraged to focus on China and Asia in a sector where start-ups and small companies have the highest potential for growth alongside a few large global enterprises.

Without a doubt, the Green Growth and Cleantech Summit increased interest and expectations. State authorities and businesses are expected to invest together in the growth of this sector and in the creation of jobs. In fact, we have already made a good start in this respect. When you take a closer look at the actual state of the sector and its potential, however, the picture gets much more varied.

Finnish professors would invest in energy self-sufficiency

At the same time, a report from an esteemed group of professors was published, addressing and offering proposals for the further development of Finland’s energy sector. The report makes fairly harsh reading. The professors came to the conclusion that Finland is losing approximately 8 billion euros a year by not seeking or investing in energy self-sufficiency. The professors criticise the national economy’s energy models, used as a basis for decisions, as outdated and rapidly requiring modernisation and openness. Moreover, energy subsidies are considered to be preventing rather than promoting the development and introduction of new and renewable forms of energy. This also results in lost opportunities for gaining valuable references in the domestic market, which are a necessity in the intensely growing global markets.

Asia? Africa? Or the same old markets?

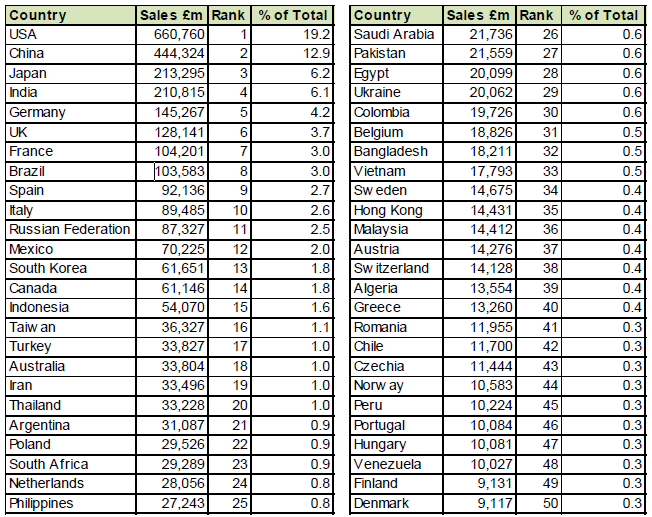

A report published jointly by the British Government and British enterprises last year makes even more gruesome reading for Finland. Finland is placed 49th among the 50 countries included in the comparison of the total value of each nation’s cleantech business. In Finland, the share is only 0.3% of the total value. The comparison, based on international standards, is the result of six years’ work. Growth figures are no more impressive. In recent years, Finland has seen mediocre growth at most, less than 3% per year, whereas Poland and the UK, for example, have enjoyed growth of 5-6%.

The same report indicates that growth potential is, in fact, highest in Africa and that similar growth is to be expected not only in Asia but also in Europe and the Americas. So, by no means is Asia the only source of growth.

Home markets and co-operation needed

The Helsinki Summit also sought to chart the bottlenecks of growth in the Finnish cleantech sector. Public procurements, more extensive domestic references and industrial and energy policy were seen as factors enabling accelerated growth.

The business sector itself is also problematic, however. Co-operation by start-ups and small companies with large global enterprises is cumbersome, largely based on dictation. New, genuine innovations and co-operation that would exploit solutions are few and far between. As stated by Konecranes’ CEO, Pekka Lundmark, the situation calls for a fresh attitude and new effort.

Recommended