2D printing is yesterday’s news. Now it’s time to buy a 3D printer. A 3D printer will produce any shape with micrometre accuracy. All you need is a blueprint that you can draw yourself or copy from an existing object using a 3D scanner. There is already a wide range of materials to choose from when printing things: plastic, metal, ceramics, chocolate, and marzipan, for example. With living cells, a 3D printer can even be used to print an actual human ear!

Advances in instant manufacturing will open new business opportunities for start-ups and experienced printing professionals alike. There is a great deal of buzz around 3D printing in the Netherlands. Based on the ideology of a sharing economy, a 3D printing service, 3D Hubs, has created a website to connect people who own a 3D printer with people who want to print objects. The 3D Hubs database of printers now includes nearly 6,000 registrations around the world, of which 68 are located in Amsterdam. This start-up gives anyone access to a 3D printer.

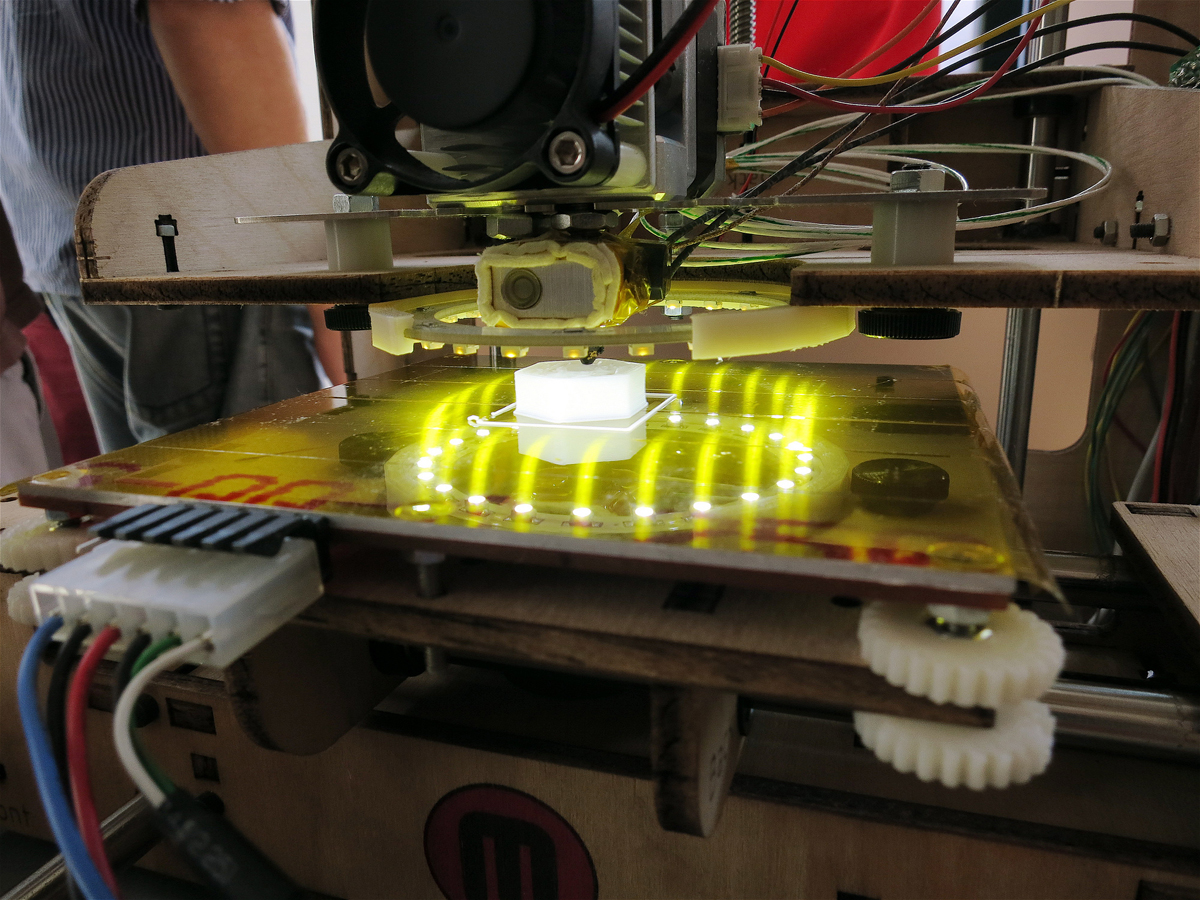

In recent years, so-called makerspaces have been formed in major cities, of which the Amsterdam-based IFabrica is a great example. A makerspace resembles a common instant-manufacturing plant, where people can utilise the same equipment and share their ideas while learning from each other in the process.

Ready-made blueprints are available on the web, and more are being added all the time. Does this mean we can soon print everything we need? Would it be a resource-wise solution?

The owners of 3D Hubs would guess that 3D printers are nowadays mostly used for printing scale models, prototypes, and, most frequently by far, all kinds of knick-knacks. Will 3D printing increase the number of useless trinkets in the world? Hardly. 3D printers are an easy way to recycle plastics. If the printing process fails, or if the produced spare part does not fit, plastic can be pulverised and reused.

As the recycling practices for 3D printing improve, at best, this manufacturing method helps ease the transition to a circular economy. Makerspaces such as IFabrica could also serve as recycling points for printable materials. How would you feel about using a 3D printer to turn your plastic packaging materials into a dish brush? It may sound weird now, but the transition to a circular economy will revolutionise the way we think about and handle different materials.

Hod Lipson and Melba Kurman‘s book Fabricated: The New World of 3D Printing lists the benefits of 3D printing: complexity and diversity do not add to the price, no assembly is required, the production lead time is practically zero, printers are portable, and side streams are reduced.

The Amsterdam-based DUS Architects is a believer in these benefits. They are currently exploring the possibilities of 3D printing through prototype elements, and the construction of a 3D Print Canal House to learn how 3D printing could revolutionise the construction industry by helping to get rid of construction waste, reduce the need for transportation, and make the actual building process cheaper, easier, and more exciting. What sounds like science fiction might just be the future.

The text is part of the ‘Resource-wise firms around the world’ blog series for discussing next-generation business concepts, business models that save natural resources and reduce emissions, and the insightful ways of marketing them.

Recommended