The report Aviation emissions (link in Finnish), jointly prepared by the Finnish Environment Institute SYKE and Sitra, provides an overview of air travel, its emissions and the methods available for reducing the emissions.

Aviation warms the climate effectively for two reasons. First, the distances travelled tend to be long. Even though, today, the amount of kerosene burned per passenger is lower than the amount of petrol used by an individual driving a car alone – in the newest aircraft less than three litres per 100 passenger kilometres – that amounts to a substantial volume of carbon dioxide emissions over distances of thousands of kilometres. Second, in the upper atmosphere other combustion products, such as water vapour, nitrous oxides and particulates, also have a warming effect.

In all, it has been estimated that the warming effect of aviation is twice as great as the effect of carbon dioxide emissions from aviation fuel alone.

For the time being, aviation is a relatively small emitter on the global scale: it produces around two to three per cent of all human-induced direct CO2 emissions. However, air travel keeps on growing strongly (at the rate of about 5 per cent a year), even though CO2 emissions should be cut everywhere at an unprecedented rate to limit global warming to 1.5°C. There are various reasons for the growth in air travel, such as the heavy subsidisation of flights – no VAT is imposed on international flight tickets and aviation fuel is exempt from tax. In comparison, taxes account for about two thirds (link in Finnish) of the pump price of basic petrol.

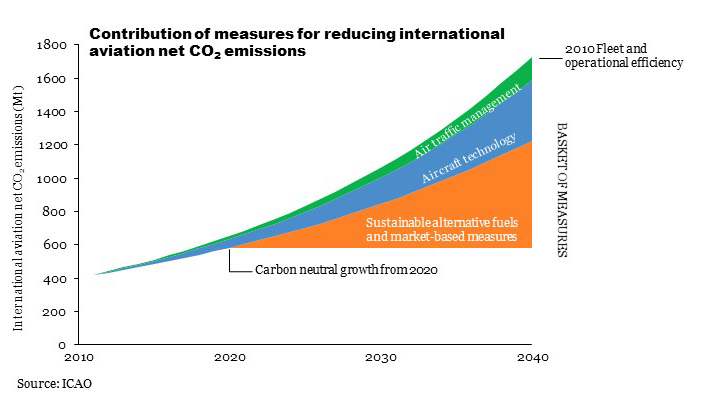

However, the aviation industry is committed to reducing its net CO2 emissions. In 2009, interest groups within the sector set it as their target to enhance fuel efficiency by 1.5 per cent each year until 2020, to stop the growth of net emissions from 2020 onwards and to cut the net emissions in half by 2050 from 2005 levels.

Carbon-neutral growth can be achieved through carbon offsetting

The standards and rules of the international aviation industry are drawn up by the UN’s specialist agency the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), its members comprised of almost all the states of the world. In 2013, the ICAO General Assembly confirmed that from 2020 onwards the growth of international aviation must be carbon neutral and, to ensure this, a global market-based steering measure would be developed. The steering measure would set a price on CO2 emissions and thus guide operators to reduce emissions where the price of doing so is the lowest.

The ICAO Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) was adopted at the ICAO Assembly in 2016. The exact CO2 emissions of the aviation industry will be measured between 2019 and 2020, and from 2020 onwards aircraft operators will offset the growth of emissions within the sector by purchasing emissions units, i.e. by funding emissions reductions elsewhere. In spite of years of negotiations, important details of the scheme still remain unresolved: so far, no agreement has been reached on the criteria for eligible emissions units or sustainable aviation fuels. However, the credibility of the whole system depends on them.

Genuine offsetting takes place only if the emissions reduction funded elsewhere is genuine, permanent and additional; in other words, it would not have happened without the sale of the emissions unit. The reduction in emissions produced by alternative fuels, on the other hand, must be examined over the whole life cycle of these products. Furthermore, the production of the raw material used for the fuels must not replace food production or carbon sinks.

The CO2 emissions from internal flights within the European Economic Area have been included in the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) since 2012. With CORSIA, the role of international aviation in emissions trading will be reviewed.

The reduction of gross emissions relies on renewable fuels

In principle, market-based measures also encourage operators to reduce the gross emissions from aviation, since they have to pay for their emissions. Aviation emissions can be reduced by three kinds of measures: operators can reduce the kilometres travelled, increase the energy efficiency – fly longer distances with the same amount of energy – or change to a lower-carbon source of energy.

Operational improvements in aviation can have some effect on the kilometres travelled and energy efficiency by such means as optimised flight routes, flight speeds and taxiing distances at airports.

Aircraft technology is the primary way of affecting the energy consumption of airplanes. And it has developed a lot: the aircraft in service today consume 80 per cent less fuel per passenger kilometre than their predecessors in the 1960s. Since the 1960s, on average, the fuel efficiency has improved by 1.3 per cent each year. To ensure that this development continues, ICAO set a CO2 emissions standard for aircraft engines in 2017. The aviation industry is also interested in enhancing the fuel efficiency for financial reasons, since fuel accounts for one third of the operating expenses of airlines.

Without an increase in passenger kilometres, the technical development of aircraft would significantly reduce aviation emissions. For example, in Finland the CO2 emissions from domestic flights have been cut in half cent since the 1990s, because the passenger volumes have remained stable while the fleet has developed. The global passenger kilometres, on the other hand, are growing more than three times faster than the energy efficiency within the industry. Therefore, the remaining option is to reduce emissions by affecting the CO2 emissions from the energy used, as depicted by the image below, published by ICAO.

Source: Traficom and ICAO.

Even aviation can be electrified, at least for short distances. For example, Norway aims to electrify all its domestic flights by 2040. For the time being, however, it would seem that battery technology does not allow the electrification of long-distance flights, because the batteries needed would simply weigh too much. However, aircraft manufacturers are continuing to explore the possibilities.

Around 80 per cent of aviation CO2 emissions are emitted from flights of over 1,500 kilometres. When seeking ways to clean these emissions, eyes turn to “sustainable jet fuels” that are currently mainly produced from vegetable oils and waste fats. In the future, the raw materials might also include different algae, halophytes and agricultural, forestry and municipal waste. The reduction in life-cycle emissions compared to fossil kerosene varies significantly depending on the raw material and the process used, but it can be up to 80 per cent. Synthetic “electrofuels” produced from carbon dioxide and water are also being developed, and the technology is considered promising. However, the production of electrofuels is still very energy-intensive, and it has not yet been tried on an industrial scale.

As a result of raw material prices, the biofuels available in the market cost three to four times more than fossil kerosene. Access to biofuels is also limited: in 2016, the production of sustainable biofuels covered less than 0.1 per cent of the industry’s overall need for fuel, and the aviation industry has estimated that in 2025, the figure may reach only two per cent. IRENA estimates that with new, advanced bio-jet fuels it may be possible to reach the aviation industry’s objective to cut aviation emissions in half by 2050, but the fuels are still at least five to 10 years away from commercial maturity. Furthermore, the necessary scaling up of the production would require significant political support. CORSIA alone is unlikely to guide operators to deploy bio-jet fuels on a large scale, since, in comparison to purchasing offset units, bio-jet fuel is expensive. Norway is the first country to have taken a decision to introduce a distribution obligation for aviation biofuels: as of January 2020, 0.5 per cent of aviation fuels sold in the country must be from renewable sources.

The most certain way to reduce aviation emissions is to reduce flying

In the short term – and, depending on the development of aviation fuels, maybe even in the long term – the only way to significantly reduce aviation emissions is to reduce flying. This is encouraged by different flight-specific taxes that are generally imposed in Europe (for example, in Austria, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, Greece and Norway). Still, the taxation on aviation has been inconsistent: for example, at the beginning of the year Sweden abolished the aviation tax it had introduced in April last year (link in Finnish). In Sweden, the previous government expected the tax to reduce air travel by two per cent. The Netherlands collected an air passenger tax in 2008-2009, and according to a survey conducted by the national ministry of transport, five per cent of the respondents said that they had changed the mode of transport or cancelled their trip because of the tax.

Do we really need to fly thousands of kilometres away from home to relax and to get away from the daily routines and busy lives?

According to a Helsingin Sanomat survey (link in Finnish), a majority of Finns support the introduction of an air passenger tax. One could assume that Finns can afford to reduce flying: according to one study (link in Swedish), Finns travel the most per capita in the world. Most of the international flights made by Finns (72 per cent) are holiday flights, the most popular destinations being mainland Spain and the Canary Islands. In the ,Tourism Study 2018 (link in Finnish), Finns reported the most important reasons for travelling as the need to relax and to get away from the daily routines and busy lives. But do they really need to fly thousands of kilometres away from home to do this?

Reducing one’s own flying this year and the next is particularly profitable with a view to reducing emissions, since this way one will contribute to the emissions ceiling under CORSIA. The average volume of the emissions from kilometres not flown in 2019-2020 will be reduced again from some other sector in the form of offsets in the coming years.

Recommended

Have some more.