1. An outcomes-based approach does not generate innovation; instead service providers play it safe and resort to using traditional methods.

The claim is both true and false.

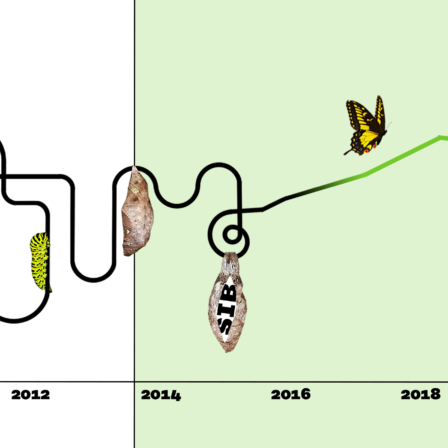

Paying for the results achieved does not automatically generate innovation. It is always the responsibility of service providers to be innovative. However, an outcomes-based approach is a way of getting service providers to look for new ways of doing things and achieving results.

A good social impact bond model is built in such a way that a service provider’s business is profitable only when its operations produce the desired results; for example, a person participating in employment training gets a job. When the funding is based on results, it is in the service provider’s interest to use various ways to achieve results and to develop new innovative operating methods.

But what is innovative about requiring that provision of services yields results? Shouldn’t a service purchased by a local authority or the state always produce results? Of course it should, but currently the results of many services are not measured and the service providers are not rewarded for the results achieved.

In employment services, for example, the usual approach is that the service provider is paid for providing teachers with specific skills to deliver a certain number of hours of training in facilities suitable for teaching. The service provider is not paid compensation based on whether the training has actually helped people find employment or not.

In the SIB model, the compensation received by service providers depends on how good the results of the service provided by them are. The model may also encourage service providers in such a way that those achieving the best results attract more customers, whereas those with weaker results end up with fewer customers.

Of course, even in the SIB model, the service provider may act in a traditional performance-based manner if it produces results. In a well-built model, activities that produce only performance without measurable results should not be profitable business.

2. SIB agreements are a new way of privatising public services.

The claim is false.

With SIB agreements, the public sector is always responsible for the operations. If the objective was privatisation, the services would be organised and managed by private companies.

The roles of various participants are clearly defined in SIB projects. The local authority owns the project and negotiates its implementation with the project administrator. The investors do not intervene in the operations in any way or even negotiate with the local authorities. In the projects, the investors are represented by the fund manager. In the SIB projects currently under way in Finland, the the asset manager acting as project manager and fund manager is FIM.

The most debated project has been the Children SIB. It develops services for children and families with children and aims to reduce the need for substantial child welfare services. People have been concerned that investors are making money out of children’s problems.

The concern is explained by the fact that SIB agreements are a new mode of operation in Finland. For example, it may have been difficult for local elected representatives to understand that in the project investors have the same objective as other stakeholders involved, i.e. to improve the services provided to children. The investors will receive returns on their investment only if the project reaches its objectives.

In Vantaa, the Children SIB has been up and running for less than a year. In the city’s experience, it is able to steer the activities of service providers better in an SIB project than in traditionally implemented procurement situations. This is possible because performance targets are precisely defined, and the city monitors how they are achieved and what kinds of methods are used for achieving the targets. Service providers and municipal employees also regularly discuss issues related to the project.

In child welfare services procured in the traditional way, the city invites tenders from service providers, and they provide certain services for the city in accordance with specific criteria.

The claim that as a result of an outcomes-based approach companies gain a strong position in child welfare services is not true. Even today, most of the child welfare services, such as child welfare institutions, are owned by companies. Furthermore, many of these companies are owned by capital investors – the private sector is already strongly involved in child welfare services.

Outcomes-based procurement is a way of steering operations more effectively in the direction of anticipating and preventing problems and strengthening the impact of services.

3. The results are impossible to measure. Outcomes-based indicators simplify problems and are set in such a manner that the public sector pays for nothing.

The claim is both true and false.

It is not impossible to measure the results. However, indicators do simplify problems, because that is what they are supposed to do. The purpose of indicators is to make problems measurable and comparable. As a rule, it requires that the problem be simplified.

Good indicators ensure availability of measurable data. For example, the number of sick leave days used in the is such an indicator. A good indicator is also objective. For this reason, the number of sick leave days is a better indicator for measuring well-being at work than, for example, an employee’s assessment of his or her personal job satisfaction.

In addition, a good indicator, at least in SIB agreements, is one that can be assessed in euros. The number of sick leave days is a good indicator in this respect as well, as the employer can estimate its cost. A functional indicator is also sensitive enough to describe the desired change, meaning that its value reacts to changes either positively or negatively.

From this point of view, sickness absences are both a good indicator and a poor indicator. In organisations, the number of sick leave days varies a lot during the year for a number of reasons. Because of this variation, it may be difficult to know what reduces the number of sickness absences. Has the number of sickness absences increased because of a worse influenza season than earlier in the year or issues related to the work community?

In SIB projects, you get what you measure. If, for example, you measure the results of a project that develops well-being at work by a decrease in the number of sick leave days, the service provider could start reducing sickness absences even at the expense of occupational well-being by always granting as short a sick leave as possible.

The service providers’ success rate is assessed according to the results of the SIB project. Often, the bonus level may also be based on the results. Therefore, selecting the indicators correctly is a prerequisite for steering and success. The indicator defines whether the targeted result has been reached or not.

It is a good idea to involve all the project’s participants in specifying the indicators in the early planning stages of the project. In addition, it may also be useful to use external experts when establishing the indicators.

The project owner ultimately decides whether it accepts the proposed indicators or not. The public sector will only pay performance bonuses if the targets set by it are met. If the indicators and their target level are set correctly, the public sector will not pay for nothing.

4. The gap between the way investment professionals and child welfare professionals think, act and speak is so great that it is impossible to create joint motivation and common goals.

The claim is false.

Despite the differences, the professionals in investing and child welfare services work together in the Children SIB project, and the work is running smoothly. In the project, the investment professionals’ point of view is represented by a fund manager; for example, in the Children SIB project the asset manager is FIM.

The perspective of municipal child welfare professionals is communicated to the fund manager through the employees of the Central Union for Child Welfare, the project administrator’s partner. The Central Union’s task is to bring an understanding of child welfare issues to the project and to act as an interpreter between local authorities and the fund.

The SIB fund investors do not engage in discussions on the content of the project with the local authorities that own the project. The approach has been adopted to ensure that investors cannot influence the practical implementation of the project, and local authorities have been guaranteed a strong position as project owners.

The co-operation between various professionals works well in the SIB project, because the goal of the project is clear. All participants want to improve the services for children and families and introduce effective practices.

The common goal encourages the parties involved to become acquainted with the way the other profession sees things and speaks about them. Professionals from both fields have had the opportunity to learn from each other’s world. They have also had to have the courage to ask questions if there has been something they have not understood.

It has become clear to the professionals in the investment industry that it is difficult to find one standard solution for all situations facing children and families, since every situation is unique.

Social welfare professionals, on the other hand, have had an opportunity to see what kind of people professionals working with money are. It has turned out that the project administrator has done what has been agreed, kept to the schedules and taken the perspectives of social welfare professionals into account.

5. Impact investing makes a profit from human distress or is just a charity.

The claims are false.

Impact investing, and social impact bonds in particular, attract investors to fund well-being services and provide new opportunities for development. Since tax revenues are currently largely spent on statutory services designed to solve problems, it is a good idea to seek new ways of financing proactive and preventive services. Impact investing is aimed not only at achieving social benefits but also at gaining financial returns; in other words, it is not a question of charity.

But what is an acceptable return on investment for an SIB agreement? The answer to this depends on the point of view. The public sector wants to limit the return earned by the investors, so that it reaps a higher share of the benefits from impact investing. Investors, on the other hand, want to ensure a sufficient return on the capital invested.

What then is a reasonable level of return from the investors’ perspective? For investors, SIB agreements are high-risk investments. In such investments, investors often bear the financial risk, either fully or partially. Furthermore, the investment method is new, there is no experience of its yield and its risks and returns cannot be compared with other investment products. The higher the risk of an investment, the higher the return expected by the investor.

SIB agreements can be compared to investing in start-up companies – the risks of investment are high for both. For the purposes of comparison, when investing in growth companies, the investor aims for annual returns.

In SIB agreements, the project owner, or the public sector, and investors must jointly find a performance bonus model in which the project’s expected return and risks are balanced and the project can be implemented successfully.

The following experts were interviewed for the article: Anna Cantell-Forsbom, Director of Family Service, City of Vantaa; Juuso Janhonen, Senior Lead, Sitra; Samir Omar, Head of Intervention, FIM; Ulla Lindqvist, Programme manager, and Riikka Westman, Project Coordinator, Central Union for Child Welfare; Irmeli Pehkonen, Specialist Research Scientist, and Jarno Turunen, Senior Specialist, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health.

Recommended

Have some more.