Bill Gates, billionaire philanthropist and technology visionary, has been a strong advocate of low-carbon technology. Most recently, he teamed up with colleagues such as Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to launch the Breakthrough Energy Coalition – a massive effort to speed up radical innovation.

As strong as his faith in innovation is his lack of trust in existing technologies. He claimed to the Financial Times that current technologies could only reduce global carbon emissions at a “beyond astronomical” economic cost.

In an interview for The Atlantic he claimed the world needs “an energy miracle”. He continued: “If we just have today’s technologies, will the world run the scary climate-change experiment of heating up the atmosphere and seeing what happens? You bet we will.”

Mr Gates is wrong. And that is good news for people and the planet.

The Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, together with distinguished partners from 10 countries, recently released the study Green to Scale. The report strived to answer a simple question: how far can the world go by simply scaling up proven low-carbon solutions?

What makes the analysis unique is the approach. Instead of theoretical potentials, we only applied existing solutions to the extent that some countries have already achieved today.

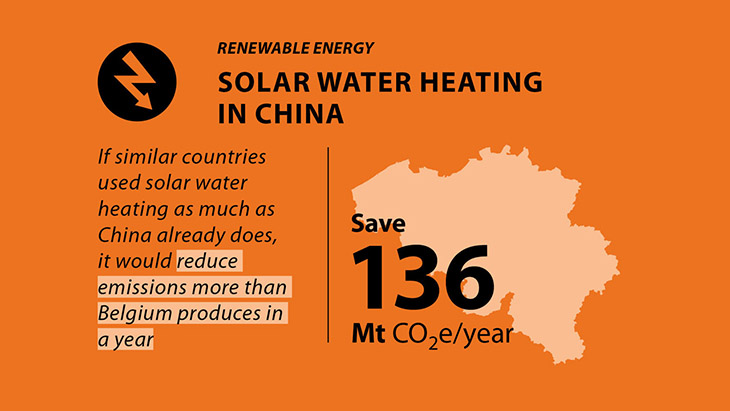

Let me give you an example. China is the undisputed leader in solar water heating. We analysed the extent to which emissions can be reduced if countries in similar circumstances reached the same level of solar collector deployment by 2030 that China already has today. Quite a lot, we found: equal to the current emissions of Belgium.

In all, we included 17 proven solutions from five different sectors. We looked at concrete cases of success stories from different countries – from Colombia to the US, from Denmark to China.

Put together, scaling up just this set of solutions can cut global emissions by a quarter compared with today’s levels. If coupled with other existing solutions, this would take us to pathways compatible with limiting global warming to a maximum of 2°C.

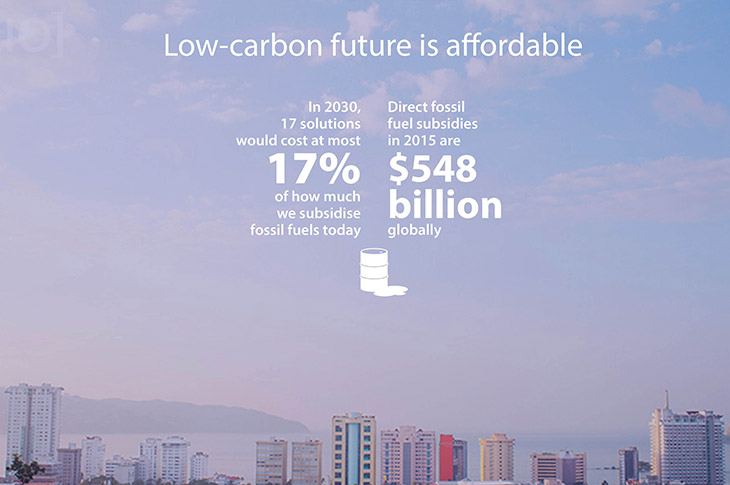

Would this happen at a “beyond astronomical” economic cost? Not at all.

The annual costs, averaged over time, would be at most $94 billion by 2030. That is equal to the GDP of the Slovak Republic or less than a fifth of the global direct fossil fuel subsidies today.

This is the pessimistic end of the cost range. The average estimate suggests that the world could actually save money by implementing these solutions.

To be clear: no new technology is required – only what we already have today. No new levels of achievement are assumed – only others achieving what some have done already today.

The Green to Scale findings are largely supported by various other studies, from the New Climate Economy reports to the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project. We can reduce emissions to sustainable pathways in the short and medium term with what we have today. We do not – and we most definitely should not – wait for miracle technologies and breakthroughs.

Mr Gates is of course right about the importance of innovation. Through innovation we can make existing low-carbon technologies cheaper and more effective. We can also uncover the solutions we will need in the long run, when the world has to reach zero and eventually negative emissions.

We need to scale up existing low-carbon solutions rapidly. And at the same time we need to invest heavily in innovation, just like Mr Gates is suggesting (and doing).

This is the recipe for winning the climate fight.

Oras Tynkkynen

This post was originally published as part of a “Nordic Solutions” series produced by The Huffington Post, in conjunction with the U.N.’s 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris (Nov. 30-Dec. 11), aka the climate-change conference. The series will put a spotlight on climate solutions from the five Nordic countries, and is part of Huffington Post’s What’s Working editorial initiative. To view the entire series, visit here.

Recommended

Have some more.