1. The limits of the earth’s carrying capacity are challenging the Nordic concept of well-being

Well-being can no longer be based on the overconsumption of natural resources and the use of fossil fuels. The global sustainability crisis may even become an existential challenge for humanity if the worst threats become reality. On the other hand, since the sustainability crisis has been caused by human activity, people can also solve it – at least in part. The solution is a transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy. However, we must start creating and implementing sustainable solutions quickly – the situation is already very urgent. And Finland is well placed to become a pioneer in leading the change.

The Nordic well-being model has been based on a paradigm of growing consumption and the assumption that we can use natural resources in an unlimited manner and produce the energy that we use with cheap fossil fuels without any consequences. As a result, our economy has been built around energy and natural resource-intensive manufacturing industry and a fossil fuel-based economy. People’s perception of what constitutes well-being has also often been founded upon the ownership of products and property.

The global sustainability crisis – the focus of which is the climate crisis, overuse of natural resources and the deteriorating functional capacity of ecosystems – is forcing us to update our concept of the economy and well-being. Societal and economic development in the 20th century was mainly achieved because of fossil fuels – oil, coal and natural gas. Fossil fuels made it possible to manufacture a great deal more products than before. Now we face a situation in which the harmful effects of this operating model have exceeded the benefits.

We need a radical change of direction from the current methods of producing and consuming energy and natural resources. At the same time, we must control climate change and safeguard the functional capacity of our ecosystems, which are important for adaptation and for producing natural resources.

The causes of the sustainability crisis are population growth and a prevailing concept of well-being that is based on ownership and material consumption. The world had a population of less than one billion in the 1850s. Now, some 170 years later, the population is around 7.5 billion and is expected to grow to around 8.5 billion by 2030 and 9.7 billion by 2050. By 2100, the world’s population is expected to be more than 11 billion. Since the mid-19th century, people have steadily pursued a higher standard of living and have wanted to own and consume more than previous generations.

The sustainability crisis has two sides: a threat and relative opportunity. The global sustainability crisis may become an existential challenge for humanity if its worst effects become reality. But if and when we begin working to first slow and then solve the crisis by moving to sustainable operating methods, this will also provide opportunities. In economic terms, the relative winners could be nations that are pioneers in terms of taking the opportunities offered by the transition and using the global market potential that it creates. Among today’s industrialised countries, the losers will be those that try to maintain and preserve old operating models.

We must move from a disposable culture that is a burden on the environment towards a carbon-neutral circular economy – and this needs to happen very quickly.

Since the sustainability crisis is the result of human activity, we also have a chance to solve the crisis through our own actions – at least in part. However, this will require rethinking and change in all of society’s activities. The assumptions and operating models upon which our economic growth and concept of well-being has been based for decades no longer work. We must move from a disposable culture that is a burden on the environment towards a carbon-neutral circular economy – and this needs to happen very quickly.

Solving the climate crisis is not only a question of how and with which fuels we produce energy. In addition to energy production, society as a whole has to rapidly become low-carbon and resource-wise. The change applies to industrial manufacturing, cities, rural areas, mobility, construction, the financial sector and the decisions made by nations. We also need to look closely at individual lifestyles: the consumption culture has to change.

The other side of the sustainability crisis is the fact that it and the efforts to solve it have created one of the world’s largest and fastest growing markets. Finland and the other Nordic countries have a great chance to gain a sizeable piece of this market, but only if we want to be crisis solvers – in other words, be one of the pioneers that create sustainable solutions and build a favourable operating environment and a functional domestic market.

2. The sustainability crisis is already here

The negative consequences of climate change are already real. Natural diversity is also decreasing rapidly. We can no longer wait for solutions.

Humanity depends on natural resources and natural activities. Ecosystem services can provide both tangible and intangible benefits, obtained from nature and valued by people. They include nutrition, medicinal substances, building supplies, recreational opportunities and other natural activities, such as ecological interaction between pollinators and plants, and purification of ground water and the air.

But ecosystem services are deteriorating as a result of the global sustainable crisis. At the same time, natural diversity has already declined dramatically. A species-poor community is less able to tolerate and recover from disruption than a diverse community.

The most important and all-encompassing factor that puts species at risk is change to their environments. This includes the construction of cities and roads, forest clearance, mining operations, field clearance, pesticide use, draining wetlands, damming rivers, the spread of foreign species, and the many and partly unidentified impacts of climate change.

We still do not know enough about the serious risks caused by the deterioration of ecosystem services and the collapse of global ecosystems. However, they may have dramatic impacts on people’s health, well-being, income or food production. A loss of biodiversity means that many ecosystems will be less capable of “maintaining” our planet by responding to phenomena such as climate change or pollution.

The deterioration of ecosystem services has not been highlighted in Finnish sustainable development discussion, and a full understanding of planetary boundary conditions has not been systematically reached either. Now we need more crisis awareness in order to make a quick societal transition possible. We use many indicators to monitor development, but the situation and its development has not been considered in relation to the planetary boundary conditions. After all, they are what clearly define the limits for a safe life on Earth.

In the future, we need to pay much more attention to ecosystem services and natural diversity, both in research and public discussion. The perspective must be expanded from the carbon footprint, moving from negative impacts to a more in-depth examination of biocapacity. Biocapacity refers to how much carbon footprint our planet can tolerate. Now while it is often suggested that Finland’s biocapacity is many times greater than the ecological footprint of Finns, in a world of global responsibility, we cannot afford to rely on this argument, because our own consumption choices also affect the biocapacity in other parts of the world.

The sustainability crisis, its causes and consequences form a very complicated web in which all phenomena – biocapacity, ecosystem services, the climate crisis, overuse of natural resources and human well-being – are interconnected.

In this memorandum, we focus on addressing the climate crisis and the overuse of natural resources, as well as the solutions and opportunities associated with them.

Emission reduction is an urgent issue

Climate change is caused by greenhouse gas emissions, especially carbon dioxide, created by human activities. Climate warming affects our life directly and indirectly, for example via its effects on the weather, the economy and our safety. It is very unlikely that any sector of life is unaffected by climate change.

Extreme weather phenomena are the most well-known effects of climate change. In some parts of the world, oppressive heat and drought that complicates food production is increasing. In other places, floods and storms and rising sea levels are causing serious problems. Climate change can also increase the spread of contagious diseases. If the extreme phenomena related to climate change become reality, wars, conflicts and refugees may become more common in some parts of the world as people fight over diminishing living space, food and water.

In Finland, the climate may be warming one and a half or two times faster than the global average and even faster in Arctic regions. The change in Arctic regions is accelerating a change everywhere in the world as the ice cover melts, revealing dark ground that binds more heat and leading to the risk of releasing more methane into the air. In Finland, the climate warms most in the winter; this means that while the growing season may be longer, pests and diseases are also moving north.

No country can flourish in a world ravaged by climate change.

Many global phenomena caused by climate change also have an indirect impact on Finland. Global warming may make large land areas in the southern hemisphere uninhabitable and create climate refugees, some of whom will also be visible in Finland. One sign of a narrow perspective on climate change is the fact that a longer growing season has been considered a positive thing in Finland. But no country can flourish in a world ravaged by climate change.

The global economic impacts of climate change have perhaps been most comprehensively studied by Lord Nicholas Stern, a former chief economist at the World Bank[1], and his working group. Stern’s report was published in 2006 and as a book the following year. It states that climate change threatens to become the largest and most extensive market disrupter in the history of humanity. Avoiding the worst effects of climate change would require annual investments equal to about 1 per cent of the world’s gross national product. If the counteractions made possible by these investments are not taken, climate change could cause a permanent drop of 5 to 20 per cent in gross national product. Although the report criticised the exaggeration of the effect of climate change in some circles, many natural scientists consider the effects of climate change to be much more serious than Stern’s estimates.

Although the climate has always varied throughout the planet’s existence, changes have occurred slowly. During the coldest periods of the last ice age that occurred 20,000 years ago, the average temperature on Earth was an estimated six degrees lower than now. At worst, we can now expect a change similar in extent to the ice age, but in a warmer direction. Another difference is the fact that the change will happen in a very short time, which means within a few hundred years. The pace of climate warming has been fastest during the past 35 years. A total of 16 of the 17 hottest years have occurred in the 21st century.[2] When climate change is too fast or too great, the earth’s ecosystems and humanity are unable to adapt to the new situation.

The global carbon budget is already tight. The carbon budget refers to the amount of climate emissions that humanity can emit into the atmosphere without causing irreparable damage. To keep global warming under two degrees, we need to limit all future carbon dioxide emissions to less than 700 gigatonnes. Global carbon dioxide emissions are currently about 40 gigatonnes per year. If emissions are not reduced quickly, we will exceed the carbon budget in less than 18 years.[3] In practice, this means that current emissions must be reduced to zero before the middle of the century, and after that emissions must quickly become negative. In other words, we will have to remove an amount of carbon dioxide equivalent to the remaining carbon budget from the atmosphere during this century.[4] The Paris Agreement also requires negative emissions from Finland in the coming decades.[5]

In June 2017, just before the G20 summit, the world’s leading climate experts published an article in Nature magazine urging countries and companies to begin fighting climate change immediately. They believe that we only have three years to take action that will achieve the targets of the Paris Agreement.[6]

Overuse of natural resources can also lead to economic crisis

If, as expected, the earth’s population grows by about 1.5 billion people over the next 15 to 20 years, three million new consumers will be classified as belonging to the middle class. According to estimates, more than 70% of the world’s population will be living in cities with populations of over 10 million by 2050. These factors will significantly increase demand for raw materials over the next 20 years, and this will be reflected in their availability and prices.

The world’s population already uses an excess of natural resources in comparison to the earth’s carrying capacity. We would need one and a half planets to sustain today’s consumption. If population growth and consumption increase according to forecasts, in 2050 we would already need two and half to four planets in order to produce the amount of natural resources required to keep us within the carrying capacity.

Over the next 20 years, the world would need an estimated 32% more energy, 57% more steel, 139% more clean water and between 178 and 249% more cultivated land than during the previous 20-year period to satisfy the needs of a growing population.[7] We have put ourselves in a position in which we are constantly consuming more and more of the natural resource stocks that belong to future generations.

However, we could already respond to the rise in population and standard of living without increasing the use of cultivated land and fertilisers by switching to smarter solutions. This means producing nutrition with the best investment–output ratio. For example, it takes more water and cultivated land to produce one kilogram of meat that the same amount of vegetable protein.

Overuse of natural resources means ensuring the availability of raw materials is becoming an exercise in self-sufficiency and competitiveness between different countries and regions. For example, 90 to 95 per cent of the rare earth metals needed in some high technology products are produced in certain areas of China. If China decided to limit exports of these rare earth metals, the electronics industry in other parts of the world could be in trouble. For this reason, many countries are now recognising the value of recovering and recycling valuable substances.

Phosphorous is another vital natural resource. Phosphorous production is mostly handled by three countries: the USA, China and Morocco. It has been estimated that known phosphorous reserves could run out in approximately 50 years. This could mean disaster for modern agriculture, which consumes a lot of phosphorous, and could even cut food production in half.

A rise in the price of raw materials would also have negative effects on economies similar to that of Finland. It may lead to a decrease in the growth potential of technology development and lower our standard of living.

3. The two sides of the sustainability crisis

Solving the sustainability crisis goes hand in hand with the economy. We need to act soon, especially if we want to retain even just the present economic conditions, to say nothing of pursuing economic growth. We need to quickly deal with the harmful negative externalities of economic growth, such as the climate crisis, overuse of natural resources and loss of biodiversity. The development of a market for clean solutions would enable a new type of economic growth.

However, solving the sustainability crisis and pursuing a new economic growth is not the only option for humanity in a world that is struggling to deal with a sustainability crisis. These options are addressed in a memorandum entitled Rewiring progress, written by Aleksi Neuvonen and published by Sitra in June 2017.

Limiting population growth and consumption to a low level is one alternative that has been suggested in public discussion. This would mean controlling population growth and halting the pursuit of economic growth, at least in developed countries. However, this option would be very difficult – perhaps even impossible – to implement. It is very unlikely that consumers in developed countries would be prepared to limit consumption based on the use of natural resources, at least at a sufficient pace. The consumption levels of the average citizen will probably remain at the same level in the near future, even if the focuses of consumption change somewhat. In order to control the environmental impacts of consumption, we need new and more sustainable products and services. There are still not enough of these products and services available on the market, but companies have begun developing them at an increasing pace. On the other hand, countries are not prepared to stop pursuing economic growth. Furthermore, it would be morally wrong to prevent developing countries from making progress and not allow the people living there to satisfy their basic needs or have access to basic commodities.

The longer we put off solving the problems caused by negative externalities, the more expensive it will be to deal with them.

Another alternative is for humanity to continue living and consuming in the same manner and let future generations deal with the harmful effects of past and present economic growth. Although our current operating model is taking us along this path, it is ethically wrong. In the longer term, it is not economically viable either. The longer we put off solving the problems caused by negative externalities, the more expensive it will be to deal with them. In this case, we may also experience irreversible changes in the climate and biodiversity that can no longer be repaired by any sum of money.

In the future, economic growth and well-being can only be based on genuinely decoupling them from overuse of natural resources and emissions.

Since the sustainability crisis has been caused by people, we can also solve it if we want to. The best option is to start dealing with the sustainability crisis quickly. This would also enable global economic growth in the future. In the future, economic growth and well-being can only be based on genuinely decoupling them from overuse of natural resources and emissions.

Genuine decoupling must also avoid what is known as the rebound effect as much as possible. This refers to a phenomenon in which people make good, sustainable choices, but the resulting benefits are used for harmful activities. For example, some of the money saved by conserving energy may be invested in new consumption that subsequently causes new emissions. As renewable energy solutions become more cost-effective, energy consumption can increase noticeably as we become complacent about using relatively emission-free energy. The rebound effect can be prevented by examining the overall effects of our activities on the environment rather than the impacts of individual actions.

The challenge of population growth and increasing consumption

The importance of solving the sustainability crisis becomes clearer when we look at population forecasts. According to a UN report, more than half of the population growth occurring by 2100 will happen in Africa, where the population is expected to double by 2050. At the same time, the strong trend towards urbanisation is expected to continue. While about 30% of the world’s population lived in cities in 1950, the number in 2014 was already around 54%, and it is expected to rise to around 66% by the middle of this century.

The problem is that global population growth is expected to mostly take place in areas where the risks of climate change are expected to be greatest, which means sub-Saharan Africa and south and south-east Asia.

Based on various estimates, 40 to 60% of the world’s population already lives in coastal areas, and the majority of the world’s megacities – those with a population of more than 2.5 million – are located in coastal regions. If living conditions near the equator deteriorate significantly due to climate change or a rise in sea level and an increase in extreme weather conditions make it more difficult to live in coastal areas, the threat of instability and both economic and humanitarian losses will increase.

A larger share of world economic growth is expected to come from developing economies in Asia and Africa. Forecasts indicate that the pace of growth in emerging economies (E7) could be double that of mature economies (G7). Economic growth in emerging economies naturally supports the growth of a young, working-age population while population growth in industrialised countries is slowing significantly or even becoming negative. This increases the dependency ratio and reduces the role that a larger workforce plays in economic growth.

Population growth and economic growth in developing countries are also closely linked to the anticipated increase in the world’s greenhouse gas emissions and consumption of natural resources. Greenhouse gas emissions are expected to roughly double over the next 50 years, and the biggest reason for this is carbon-intensive industries in developing countries.[8]

Solution-related markets

Emerging economies will not necessarily have to take the same path of wasting natural resources that has been followed by industrialised countries.

The population and economic development paths described above also represent amazing opportunities. Switching to a low-emission society will create enormous economic potential, and emerging economies will not necessarily have to take the same emission-intensive path of wasting natural resources that has been followed by industrialised countries.

The World Bank estimates that controlling climate change with smart planning in the transport and energy-efficient sectors would, calculated in terms of growth in gross national product, produce an added benefit of 1,800 to 2,600 billion dollars in 2030

(in comparison to a situation in which no action is taken). This could also prevent 94,000 premature deaths each year.[9]

The New Climate Economy group, which is made up of economists and political decision-makers, has estimated that in normal economic development conditions investments of approximately 89,000 billion dollars will be made in the global infrastructure from 2015 to 2030. If we want the new infrastructure to support the transition to a low-carbon society, 4,100 billion dollars should be added to that sum.[10]

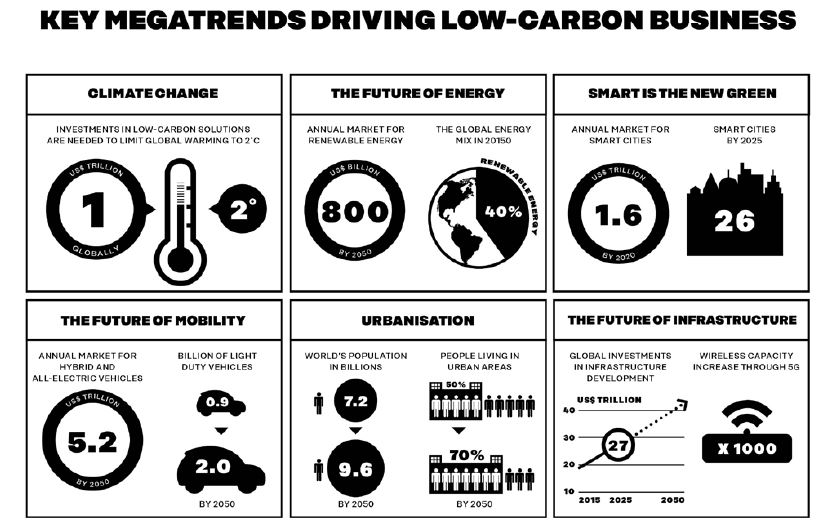

In a report published in 2015, Sitra and the Frost & Sullivan consulting company assessed[11] the future prospects for the cleantech market, which is an important area for Finland. This extensive analysis of global markets for clean and smart solutions until 2050 shows that the most important megatrends in relation to low-carbon business are climate change, renewable energy, smart green solutions, low-emission future mobility, urbanisation and infrastructure development (see figure 1 and the box below).

The common denominator for the megatrends mentioned above is smart cities. Large cities make it possible to bring huge numbers of people within the scope of new, low-emission operating models in a smaller physical area. These cities can function as test and development platforms for low-emission and resource-efficient solutions.

Cleantech markets – with the exception of the low-emission transport market – are expected to increase significantly to become worth nearly 3,000 billion dollars per year by 2050. The Nordic countries and Finland can be pioneers and – in relation to their size – can take a larger role in developing resource-efficient and smart solutions and offering them to these markets. There are already major global markets for low-emission transport and electric cars. And, as indicated in the box above, these two markets are expected to grow into an annual market worth 4,700 billion dollars, a staggering growth when one considers that the value of these two in 2014 was a mere 597 million dollars.

These individual forecasts illustrate the size of investments that humanity will need to make in order to control the sustainability crisis and achieve economic growth that is compatible with the limits set by the earth’s carrying capacity. The countries and companies that can develop smart, low-carbon and resource-wise solutions will achieve the greatest benefits from these rapidly growing markets. Countries and companies that resist and hinder change will be left behind.

4. The building blocks for a carbon-neutral circular economy

If we do not start solving the sustainability crisis soon, the cost of repairing the damage will be even higher.

The transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy must begin quickly because there is no time to waste. If we do not start solving the sustainability crisis soon, the cost of repairing the damage will be even higher. Failure to act would take us towards a tipping point, after which no amount of money in the world would be enough to repair the damage.

Solving the sustainability crisis will require greater ambition in international agreements and rapid implementation of what has been agreed, the creation of a domestic market for the carbon-neutral circular economy at the national level, and rapid scaling up of existing solutions at the same time as new disruptive solutions are developed. In addition, land use must be replanned to maximise carbon dioxide fixation from the atmosphere; in other words, to increase negative emissions.

The problem with the sustainability crisis is not a lack of recognition, but that the sustainability crisis is not being taken seriously enough and action is being delayed. Right now, the world has a shortage of crisis awareness.

More ambitious international agreements

A new and comprehensive climate agreement was reached at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the UN’s Climate Agreement held in Paris in December 2015. For the first time, nearly all the world’s countries stated that they were ready to take action to prevent climate change. Unfortunately, the United States announced its withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement in 2017 after President Trump’s government took office. This announcement sparked a strong reaction around the world. The main message in the reaction was that other countries will continue working to limit global warming to the level required by the Paris Agreement. Only the future will reveal the genuine reaction of other countries, such as Saudi Arabia, to the USA’s withdrawal.

The aim of the Paris Climate Agreement is to keep the average global temperature rise well below two degrees in comparison to pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees. In addition to emission reduction targets, the agreement sets a long-term goal of adapting to climate change and a goal of allocating financial flows to low-carbon and climate sustainable development. The parties’ progress in relation to the goals of the agreement will be examined every five years, with the first full review taking place in 2023.

International climate agreements, including the Paris Climate Agreement, have been criticised for their slow pace of implementation. However, international agreements are the only way the world can set a common goal and schedule for reducing emissions globally. At the present time, the pledges made by different countries to reduce emissions are not ambitious enough to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Although the European Union is known as a pioneer in the use of low-emission energy, it must also update its climate targets to comply with the Paris Agreement. A report published by Sitra and Climate Analytics in 2016[12] reviewed the ambition of EU and Finnish emission reduction commitments aimed at meeting the targets of the Paris Agreement. Models that optimised fairness and the economy were used in the process. The economically optimised model examines emission paths that are economically and technologically viable and that minimise overall global costs. The fairness model looks at how a country’s emission reductions compare to those of other countries using a range of fairness indicators, such as historical responsibility for climate change and ability to reduce emissions.

According to the report, the fairness model shows that the EU should reduce emissions by at least 75% instead of the current 40% target by 2030 and by 164% by 2050. Based on the economically optimised model, the EU’s emission reduction targets should increase to 50% in 2030.

In order to do its fair share, Finland’s emission reduction target in 2030 should be 60% instead of the current 50% and the target in 2050 should already be 152%! This means that Finland would have to remove more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than it produces.[13] We can achieve negative emissions by, for example, maximising carbon sequestration in the forest and soils or by developing technical solutions for carbon capture and use or storage. According to the economically optimised model, Finland should reduce its emissions by about 60% by 2030 and 130% by 2050.

The idea that a small country’s emissions have little meaning on a global scale is still quite prevalent in Finland. Many believe that only the actions of countries with high emission levels are important. Although Finland has a small carbon footprint, an ambitious domestic market can help it become an important global operator by creating solutions for the world market (increasing what is known as the carbon handprint). Ambitious climate targets would challenge companies to compete against each other with efficient, low-carbon solutions that could also be sold to other countries.

Better use of existing solutions

The urgent need to deal with climate change is clear and there is no time to waste. This means using all possible methods to reach the target. We need new incremental and disruptive innovations to reduce emissions. Incremental innovations help us to reduce emissions and consumption of natural resources with existing operating models. On the other hand, disruptive innovations change our whole way of operating. We need to invest in research and development work to develop both types of innovations.

The challenge involved in controlling climate change is that research and development investments only begin producing results after years of work, while the critical time in terms of controlling climate change is right now. The timeline from research to widespread implementation is frustratingly long with regard to climate change. This is why it is so important to not only develop new solutions but also make full use of existing solutions to reduce emissions.

The Green to Scale report[14] published by Sitra in 2015 examined the emission reduction potential of existing solutions. The report analysed 17 proven emission reduction solutions from around the world and found that scaling solutions from countries where they are already used to comparable conditions could reduce CO2 emissions by 12 gigatonnes by 2030. This is equivalent to one quarter of the world’s emissions. No new inventions are required, nor vast amounts of capital. Scaling up these 17 solutions that have already been proven in one country for use in other comparable countries would also result in net savings over time, as investment costs can be offset in particular by efficiency measures that deliver reduced energy bills.

The Nordic countries can also help other countries reduce their emissions. The Nordic Green to Scale report[15], published in 2016 as a continuation of the Green to Scale report, analysed examples of scaling up emission reduction solutions in the Nordic countries. The report found that scaling up 15 Nordic climate solutions for use in comparable countries could reduce emissions by 4 gigatonnes by 2030, which is an amount equivalent to all current emissions from EU countries. In addition to direct emission reductions, widespread implementation of these 15 solutions would also provide other significant benefits. For example, they would improve air and water quality, increase the number of local jobs, improve energy security, cut fuel costs, reduce traffic jams and help retain natural diversity.

Although the world also needs completely new solutions to reduce emissions quickly, existing solutions should be better utilised at the same time. The need for innovations and new technology cannot be used as an excuse for delay, and the available solutions must be implemented now.

In addition to research and development work, public investments are needed to ensure that new solutions can be piloted and have access to markets. This does not always mean more or “new financing”, and existing financial instruments should also be refocused. For example, the government and municipalities in Finland spend approximately 30 million euros per year on public procurements. Unfortunately, even when new and better solutions are available, these procurements often focus on old solutions that may be a burden on the environment. Promoting the implementation of new, low-carbon solutions through public procurements could decrease greenhouse gas emissions and support the operating conditions and development of the cleantech market. This would help create jobs and support companies who obtain their references from the domestic market to access growing world markets.

Turning Finland and other Nordic countries into model circular economy countries

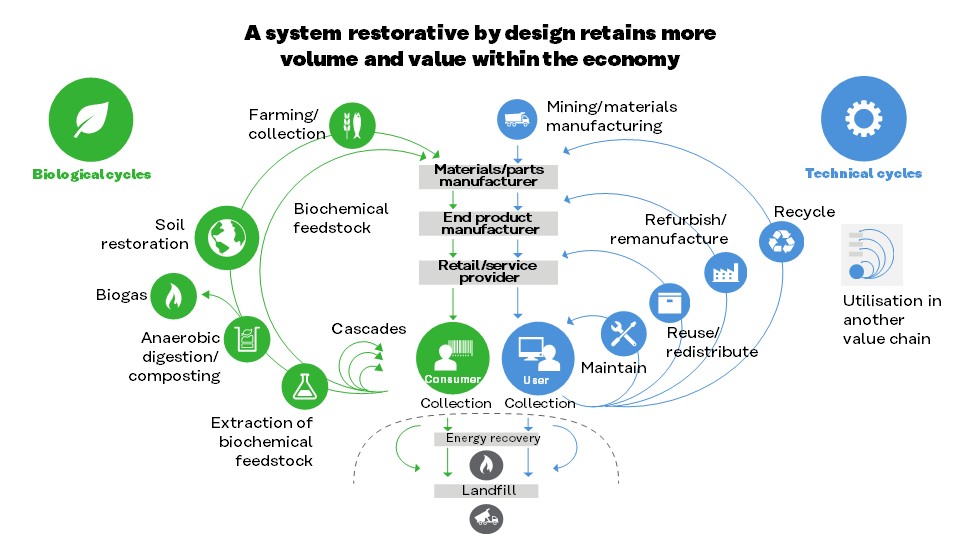

A circular economy, which prevents overuse of natural resources and promotes a move away from a fossil fuel-based economy, would provide at least a partial solution to the climate crisis. A circular economy is the opposite of the current linear economic model, which involves using more and more natural resources to produce products that end up being burned or going into landfills too quickly. Circular economy solutions can cut climate emissions by up to one half in certain sectors, increase well-being and promote the renewal of society and, as a result, competitiveness.

In a circular economy, materials are used more sparingly, which means producing products that remain in circulation and retain their value for as long as possible or even increase in value while in circulation. The aim is to turn waste and side streams into products with a higher refinement value. This keeps loss and waste to a minimum. In a circular economy, product manufacturing from virgin raw materials is replaced by maintenance, reuse and recycling.

Smart solutions and digitisation are the focus of the circular economy. Intelligence creates added value for products, and digital solutions enable products to be seen more as services. This way, people receive the benefit of a product by buying it as a service and removing the burden of having to own and maintain the product themselves. Product-as-a-service business models make it possible to improve resource efficiency because products are used more frequently and it is in the service provider’s best interests to manufacture long-lasting and durable products rather than disposable ones. The manufacturer’s profits no longer come from selling large numbers of products but from offering services related to long-lasting products.

A circular economy also increasingly aims to replace non-renewable raw materials and fuels with renewable ones. The best-known concept of the circular economy is illustrated by the “butterfly” diagram, published by the Ellen McArthur Foundation in 2011. It illustrates the circulation and added value logic for biological and technical materials.

The transition to a circular economy is inevitable as population and consumption increases, but it also represents an opportunity for a new type of economic growth. The size of the global circular economy market has been estimated at 1,800 billion euros per year. One per cent of this would be 18 billion euros, which is not an impossible goal for Finland. In terms of European industry, a circular economy is expected to provide savings of 600 billion euros.[16] The circular economy service business models used to keep materials and their value in circulation could create millions of jobs in Europe and tens of thousands in Finland.

However, a lot of work is still needed to achieve a truly functional circular economy. It has been estimated that about 70 per cent of the materials used by the global economy each year (including energy production) are what are known as throughput materials, which means that they do not continue as products or they are not recycled.[17]

Finland has a good opportunity to be a model country for the circular economy, because some circular economy principles have already been in use in areas like the forest industry for many years. In 2016, Finland also compiled the world’s first road map to a circular economy, a process that was co-ordinated by Sitra. More than 1,000 people from different sectors of society participated in the road map preparation process. Selected on the basis of Finnish strengths, the focus areas of the road map are a sustainable food system, forest-based loops, technical loops, and transport and logistics. The road map strives to combine administrative actions with concrete projects at the grass-roots level. This road map emphasises tangible actions for growth, investments and exports.

Road map implementation is directed by the steering group for the circular economy in Finland, co-ordinated by Sitra, and dozens of organisations are involved in its implementation. The aim is to promote close co-operation between the public and private sectors in order to accelerate the transition towards a circular economy. In order to create a circular economy society, we need a new kind of expertise, cross-sectoral co-operation, development of the operating environment and – from companies – a change in attitudes and operating methods. The aim of the road map is to create at least 3 billion euros in added value for Finland by 2030, create thousands of new circular economy jobs, accelerate export and share best practices with other countries.

The actions of individual countries and national plans, such as Finland’s road map to a circular economy,[18] can serve as examples in the global transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy. The global transition can be accelerated by international agreements, legislative measures and by creating a domestic market that encourages the development and scaling up of new solutions.

Finland and the other Nordic countries can set an example for other countries by creating sustainable and comprehensive operating models for implementing a circular economy, and by trying to increase understanding of the sustainability crisis and its consequences, which include the interdependence of climate change, dwindling natural resources and a sixth wave of extinction. The sustainability crisis is a consequence of how we have produced and consumed materials and energy. Just as important as dealing with the consequences is trying to solve the root causes: how we can change our ways of consuming and producing products and energy. Perhaps the most important question is how we could change people’s concept of well-being so that perceived well-being and happiness would no longer depend only on owning products and having more opportunities to consume.

Sustainable land use as the foundation for the carbon cycle and resource wisdom

Land use and food production cause many environmental problems, from climate change to diminishing biodiversity. Consumption of the food produced is not equal either. Eight hundred million people in the world go hungry and 600 million people are obese. The food system affects all societies. Two billion people work in agriculture, and many of them are poor women. The growing population and the rise in the standard of living is putting pressure on land use and forests. On the other hand, 12 countries in the world (including Algeria and China) have succeeded in increasing their forested area while simultaneously improving food security for citizens.

The key question in food production is: how can we guarantee safe and healthy food for consumers in a way that minimises the environmental impacts? The right answer is not the oft-quoted “we should produce more food”. The so-called green revolution took place in the 1960s. This was when artificial fertilisers significantly increased the size of crops. Now, we need a more genuine green revolution, involving the use of carefully optimised sustainable investments in food production and land use.

Food production has many major impacts on the environment. In addition to food security and security of supply, this is an important factor to consider when developing a sustainable food system. The system has to use nutrients in an efficient and recyclable manner. The climate crisis is making water management more important, because drought is more common in certain regions while extreme weather phenomena, such as heavy rain, are increasing in others. Observing circular economy principles makes it possible to produce food in a smarter way with the existing farmland. We need to avoid clearing new fields. However, this continues to happen, in Finland too.

Today, global food production is very dependent on fossil fuels. The share of renewable energy must be increased in production. This means more organic fertilisers and more renewable sources of energy for running agricultural machines or drying grain.

Meat production places a much greater burden on the environment than vegetable production.

Meat production places a much greater burden on the environment than vegetable production. In terms of nutrition, people in Finland and many other developed countries eat too much animal-based food. In particular, reducing the consumption of red meat and increasing the use of sustainably produced vegetables can decrease the environmental burden caused by food production and also improve public health.

The challenge facing the current food system is the fact that a big part of the food produced (about 30% globally) is wasted, meaning that many of the harmful effects of production are generated unnecessarily. Waste occurs in different parts of the food system. In developed countries, the majority of waste comes from catering services and private households. In less developed areas, crops produced in fields are often lost during harvesting, processing and storage.

As the population grows, the need for sustainable food solutions becomes more acute. However, climate change will limit production in many of today’s production areas.

Agriculture is often made the scapegoat with regard to environmental pollution and climate change. On the other hand, agriculture, soil health and sequestering carbon in the soil have an important role in controlling climate change and adapting to change. Healthy soil is also more productive than unhealthy soil. The importance of soil has already been recognised: initiatives to this effect have been undertaken and projects launched. One of these is the “4per1000” initiative, highlighted by France at the Paris climate conference. It is intended to increase soil carbon stocks by 4 per mille each year. This is equal to all annual greenhouse gas emissions from human activities globally.

The role trees play as carbon sinks is well known, at least in Finland. Forests are also diverse living environments that are important for water circulation and soil health.

Forests can be used to slow climate change by increasing the amount of carbon sinks and stocks. Good forest management and effective control of logging can increase carbon sequestration and carbon stocks can be increased through the manufacture of longer-lasting wood products. Currently, about half of Finland’s annual carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel energy production are sequestered in trees, forest soil and wood products. The Paris Climate Agreement acknowledges the role of carbon sinks in controlling climate change. According to the agreement, global greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sinks must be in balance in the latter half of this decade. A significant amount of negative emissions will be needed at the end of the century, and one way of achieving this is maintaining and increasing forest carbon sequestration.

Some 86 per cent of Finland’s land area is classified as forestry land, making forests and the forest industry very important to Finnish society. However, public discussion of forests often focuses only on the timber available from them. Greater emphasis should be placed on the strategic goal of maximising the overall value of Finland’s forest-based products and services rather than the amount of timber used. Ensuring natural diversity in forest use is also important. This can be achieved by various forest management methods.

5. The transition represents opportunities

The transition to a new sustainable economy will be a major undertaking with profound consequences, so it is clear that there will be winners and losers. The losers will be traditional industry and those operators unable to renew and adapt fast enough. The winners will be those that create new, sustainable solutions with concepts and products that have wide-scale international appeal as well. The government’s task is to encourage industries and operators to adapt quickly.

A key element in this is eliminating old subsidies or redirecting the ones that are retained. Finland also spends about 2 billion euros per year on environmentally harmful subsidies that sustain old operating models and slow the upcoming transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy.

The transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy is inevitable. This is why the government must develop mechanisms that can facilitate the transition in areas such as commerce and the corporate world. Lifelong learning can be one method of providing better opportunities for companies and their employees to create new operating models.

We should not try to prevent or slow an inevitable change too much, because this can lead to poor investments in transport or energy production that may become very expensive for society. The transition can be made easier by implementing it in a controlled, step-by-step manner with regulations and incentives that give everyone time to adapt to the change and prepare for it in advance. Unpredictable regulations and incentives and denying the need for the transition will be disastrous for the economy, companies and individuals.

A comprehensive change in infrastructure

The transition to a sustainable economy will require major infrastructural changes. The biggest changes will be needed in cities, in energy production and in transport systems. The following section contains a brief review of the type of changes taking place in these areas and what is still needed.

1. CITIES PLAY A DECISIVE ROLE

Cities currently consume more than 70 per cent of the world’s energy and produce an equivalent amount of greenhouse gases. It is often said that cities will determine the future of the planet. In order to solve the climate crisis and prevent the overuse of natural resources, cities must rapidly change their entire infrastructure to a low-carbon and resource-wise model. They must serve as platforms for developing and implementing new solutions and convince inhabitants to take action to achieve a carbon-neutral circular economy by making it easy for people to make sustainable choices.

As countries have delayed, cities have begun to lead the transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy. Thousands of cities and towns have put low-carbon targets at the core of their strategies and have committed to emission reduction.

2. ENERGY PRODUCTION MOVES TOWARDS ZERO EMISSIONS

Global energy consumption continues to grow at an enormous pace. Over the past 25 years, the global economy has doubled in size and energy consumption has increased at the same rate. Most of the increase in energy consumption has occurred in developing countries, especially in China, where hundreds of millions of people are moving from poverty towards a Western standard of living.

However, fossil fuels cannot be consumed at the current pace for two very simple reasons. First, oil, natural gas and coal reserves will simply run out. Second, we are well aware that the majority of the known reserves cannot be used if we want to stop climate change. This is a huge challenge, but our only choice is to try to respond to it. Humanity must find more sustainable ways of producing energy.

Energy production plays a key role in solving the climate crisis. A system based on fossil fuels produces two thirds of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions. Historically speaking, the change required in the energy system will be exceptional in terms of both scale and time frame.

That change is already beginning. Many large corporations are striving for renewable energy production, and companies and investors want to start a renewable energy and circular economy revolution. Non-governmental actions make it easier to achieve the national emission targets set by countries and also make climate policy as a whole more ambitious.

The change is supported by the rapidly decreasing costs of low-emission energy forms, especially wind and solar energy. New calculations show that onshore wind power also became Finland’s cheapest form of energy production in 2017.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), scaling up energy efficiency and renewable energy will provide the largest emission reduction benefits in future decades. Carbon capture and storage technology and nuclear power, especially during the transition, is likely to be needed as well. The change will require a redirection of policy and financing to comply with climate targets.

Although Finland’s climate targets are still not enough to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, Finland and other Nordic countries are already close to the world’s leading countries in terms of implementing renewable energy. Among other things, Finland intends to be the first country in the world to stop using coal by 2030 and to ban its use in energy production after that. However, Finland should also put more effort into developing and implementing solar and wind energy and especially into energy storage solutions. A quick schedule for bringing electric cars to the market would support the development of electricity storage. Finland should also make more use of demand response, which could balance the peaks in demand when electricity is at its most expensive.

3. TRANSPORT NEEDS A REVOLUTION

Until now, global mobility has mainly been based on the use of fossil fuels. Transportation causes about 20% of the greenhouse gases that increase climate change in Finland and 14% of global climate emissions. According to the Finnish Information Centre of Automobile Sector, the number of cars in Finland alone increased from 27,000 to more than 3 million between 1940 and 2016.

More than 90% of transport emissions in Finland comes from road transport. In terms of sustainable well-being, other challenges associated with transport are factors related to pollution, congestion and comfort in cities – after all, a lot of potentially valuable land in cities has been converted into roads – and the cost and inefficiency of mobility, accidents and wasted logistics capacity. A transport revolution, which means switching to a transport system that is powered by something other than fossil fuels and mobility based on shared resources would allow us to achieve ecological sustainability, as well as high levels of well-being, the effective use of time and major economic benefits.

The ways in which we move around and transport goods are on the threshold of a new era. The change in transport will be huge, even compared to the impact created by the emergence of mobile phones and the internet, and we are already starting to see the early signs. When new transport services, automation and electric cars become commonplace, we will be able to talk about a revolution rather than a gradual modernisation of cars and infrastructure development. A significant decrease in the number of cars also appears likely in future decades.

According to calculations made by the International Transport Forum at the OECD, the number of cars in medium-sized European cities may drop to as little as one tenth of the current level as a result of automation and service development.[19] In the most optimistic scenario, transport in the Helsinki region could be handled with just 3 or 4 per cent of the current number of vehicles if the cars were used efficiently.[20] Mobility based on private cars will decrease radically, because service-based and optimised alternatives will reduce mobility costs by 60 to 80 per cent in comparison to the current level.[21] A major decrease in the number of cars should already be taken into consideration in town and facility planning.

Finland has an excellent opportunity to be an international pioneer in the transport revolution: our country is a suitable size for testing and scaling up models. Favourable legislation, technological competence and open-minded mobility service start-ups can and will promote this pioneering role. The viewpoint of transport service users will also become more valued and bring new dimensions to transport.

The propulsion methods used by vehicles need to change as soon as possible in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions caused by transport. Electrification is progressing steadily around the world, and this should be supported in Finland by developing a charging infrastructure. It is also important to promote other alternative propulsion methods, such as biogas. The most reliable solution would be for Finland to have an infrastructure based on several different modes of propulsion. However, it is not enough to only renew vehicles and change the modes of propulsion – we need to move to a new and comprehensive transport system.

The change in transport can happen very rapidly. The question is whether we will be pioneers or adapters. Is our shared vision one that involves a number of small improvements to the existing system or a comprehensive renewal of future mobility? Instead of developing public transportation and private cars as separate entities, we must consider using shared resources for passenger transportation. New transport services will become a seamless part of public transport as a result of a sense of community, sharing and digitisation. The rewards can be lower emissions, congestion and costs, improved safety, more enjoyable living environments and health benefits.

Minimising the carbon footprint and maximising the carbon handprint of companies

The business sector can increasingly create clean and efficient solutions for the government, cities and individuals, and has already begun to challenge governments to implement more ambitious climate and environmental targets and action by demonstrating new solutions.

The background to the ambitious level of the Paris Climate Agreement was strong support and encouragement from business pioneers. After Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, a large group of corporations and important investors appealed to the United States to remain in the climate agreement. The greatest concern of companies and investors is that companies will be left out of one of the fastest growing markets if the United States leaves the Paris Agreement. Many important American companies have announced that they will continue developing clean solutions despite the country’s decision to withdraw from the agreement.

Companies are already competing with each other by creating more efficient and cleaner consumer-centred technologies and services. At the same time as pioneering companies try to solve the world’s biggest challenge – the sustainability crisis – they are doing profitable business and providing export income for their countries. Governments need to create an operating environment that encourages companies to renew and adapt while also getting rid of old structures and operating models. One way of doing this is through subsidies.

A good example of the opportunities created by legislation is the blending obligation that applies to the renewable fuel component in transport. A few years ago, the European Commission set a blending obligation requiring that 10% of all transport fuel must be renewable fuel. Finland wanted to set a more ambitious target and raised the blending obligation to 20%. As a result, domestic companies began to develop their own biofuel production technologies. A favourable domestic market turned Finland into one of the world’s leading biofuel producers.

In addition to reducing their carbon footprint, companies can also increase their carbon handprint. Carbon handprint refers to the positive climate and environmental impacts of products and services. Finnish companies have outstanding possibilities to produce solutions for the global sustainability crisis. Environmental attitudes in the business sector have changed a lot in Finland in recent years. Just 5 to 10 years ago, many companies perceived strict environmental and climate norms as a cost factor and a burden, but today these norms are often seen as a competitive edge. Strict environmental and climate legislation motivates companies to compete through cleaner and more efficient solutions that also have great export potential.

In 2015, a group of major Finnish companies and Sitra established the Climate Leadership Coalition (CLC), in which the participants work together to find solutions to the global sustainability crisis and encourage the Finnish government to create a favourable environment for doing so. At the beginning of 2017, the CLC already had 35 member organisations.

Redirection of financing to accelerate the transition

1. REDIRECTING PUBLIC AND INSTITUTIONAL FINANCING

Emission reductions and adapting to the effects of climate change will require capital. Climate-related financial flows from public and private sources have begun to increase in recent years. This change applies to financing granted by governments and development finance institutions. Governments must find ways to reduce ineffective fossil fuel subsidies and increase the costs of polluting by means of carbon pricing. Together, these measures will help to shift investments from old, polluting ways to cleaner solutions.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that during the next 20 years energy sector investments will be 48,000 billion dollars, or about 2,400 billion per year. The redirection of current investments represents a huge energy revolution opportunity. What if that money was used to redirect investments that would be made in any case to low-carbon alternatives? If investments are planned in a wise, long-term manner, they can create more efficient and smarter future solutions that produce lower emissions without significant additional costs. This is a choice between two future paths. How can that huge amount of capital be steered towards low-carbon forms of production? According to the IEA, the change will require at least the steps described in the following box.[22]

Many initiatives have been taken around the world with the aim of better quantifying environmental factors as part of decision-making. They include requirements for institutional investors (divestment movement), many voluntary initiatives to measure environmental impacts (Principles for Responsible Investment, Global Reporting Initiative and Montreal Pledge), external pressure from stakeholders (including non-governmental organisations), and consumer and owner demands for ethical operations and climate actions on the part of companies. Together, these requirements are pushing investor decision-making in a direction that would enable both returns and a balancing of long-term risks.

2. PRIVATE FINANCING TO DRIVE SUSTAINABILITY

Since the Paris climate conference, investors appear to be even more committed to controlling climate change. In May 2017, after the United States had threatened to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, a group of more than 200 large institutional investors managing an estimated 15,000 billion dollars in wealth appealed to decision-makers in G7 countries to keep their promises to control climate change.

In general, investors’ interest in responsible investing is on the rise and more than 1,700 organisations, which manage tens of billions of dollars in wealth, have already signed the UN’s Principles for Responsible Investment. Many investor groups[23] have also started to produce information on the impacts of climate change for investors.

Investors’ interest in climate change is also evident in the increased use and development of data collection methods detailing the environmental and climate impacts of companies. Investors need information on assessing the climate risks and impacts of their investments, and there are now many providers of such data and analysis services in the market. One of the biggest is the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). This organisation has increased its membership from a few dozen investors in 2003 to more than 800, who now manage assets worth more than 100,000 billion dollars. According to its own information, more than 5,600 companies and 533 cities report to the CDP on their climate and environmental impacts.

As general awareness of climate change has increased, assessment of its impacts has become part of the analysis processes of investors. At the same time, low oil prices and pressure exerted by non-governmental organisations on investors and companies has forced many investors to consider the future of fossil fuels in investment portfolios. Estimates indicate that investors representing more than 5,000 billion dollars of wealth have committed to exclude fossil fuel companies from their investment portfolios.[24] At the general meetings of coal and oil companies, important investors have also demanded estimates of the impacts of climate change on business and policies to control climate risks.

Investments in low-emission solutions are increasing. In 2016, more than 118 billion dollars in standardised “green bonds” and 694 billion dollars in climate-aligned bonds were issued. The assets acquired with them are being used to finance low-emission infrastructure projects.

A variety of share indices and funds have also been developed for investors, making it possible to invest in, for example, renewable energy. A greater number of climate-friendly or low-carbon investment products means that it is easier for investors to make investments that decrease their carbon footprint and increase the amount of financing available. According to the Global Climate Index 2017 report, the majority (over 60 per cent) of the world’s 500 largest investors paid attention to climate change in their investment activities for the first time.

Investors around the world are gradually beginning to take climate change seriously.

Investors around the world are gradually beginning to take climate change seriously. The risks caused by climate change and the business opportunities provided by preventing climate change and developing low-carbon solutions are being examined systematically and as a part of normal investment analysis. Cash flows are turning away from fossil fuels.

Individuals as drivers of sustainable consumer markets

It is also time for people to update their understanding to better suit a situation in which they learn to adapt to the limits set by the earth’s carrying capacity. The ways in which people live, travel, eat and consume have significant environmental impacts. The choices made by individuals will eventually be responsible for the majority of global emissions. This is why they are the most important drivers of natural resource consumption. It is often said that individuals alone cannot solve the sustainability crisis, but it certainly will not be solved without them either. Having said that, many studies show that a lifestyle founded upon an appetite for consumption and ownership does not always provide well-being and happiness.

According to the Resource-wise citizen survey conducted by Sitra,[25] 72 per cent of Finns believe that acting to save the environment is important, if only for the sake of setting an example. However, less than half have consciously reduced their consumption for environmental reasons and tried to make more responsible choices. This means people are highly aware of the issues related to the environment and ecological sustainability, but attitudes and values move slowly from words to action.

Only a fraction of people make consumption decisions based solely on environmental issues. It is also important to take economic savings, health benefits and increased leisure time into account.

People easily gravitate towards a lifestyle that is pleasant and easy. Psychology and sociology have demonstrated that we tend towards irrational decisions and habits even when we know that our lifestyle has a negative effect on natural resources. However, the ease of modern life has an unsustainable price tag. People are more prepared to change their attitudes in the direction of prevailing behaviour than against it. Only a fraction of people make consumption decisions basely solely on environmental issues. This is why it is more realistic to inspire consumers by promising them economic savings, health benefits or increased leisure time.

In addition to laws, regulations and taxes, we need less heavy-handed ways of solving problems caused by the choices made by people. According to various studies, proven methods of exerting influence include the following “nudges”: environmentally friendly default options, reminders and simple instructions; making it easier for people to make ecological choices; and sharing information about the model behaviour of others.

The way to the heart of a consumer is through the services and goods that companies offer for everyday life. The most successful circular and sharing economy companies have succeeded in communicating the environmental benefits of products and services and satisfying customer needs. Although consumers are increasingly aware of the ethical factors and environmental burdens associated with products and services, there is still room to improve attitudes. Only 15 per cent of respondents to Sitra’s Resource-wise citizen survey said they had begun to lend things to others more, while at the same time more than half of them are not in the habit of borrowing or hiring things instead of owning them.

Better health, tasty and good food, less stressful daily physical activity, saving money and material recycling as part of profitable business are examples of factors that can promote sustainable consumption and lifestyles. Good habits become more established if we describe and show how others live according to them.

Companies and communities also need to be challenged to speak on behalf of a more desirable and sustainable lifestyle. The glorification of extravagant consumption – in particular a disposable culture – and things such as unnecessary sale days for shopping could be ended. A smart consumer takes the necessity, lifespan and environmental friendliness of acquisitions into consideration.

6. Practical solutions and future needs

We need to start solving the global sustainability crisis immediately because there is very little time left. If this cannot be done, we risk losing the foundation for everything else, such as the economy, security and well-being. The solution is internationally binding agreements and national policies that apply to all sectors of society. They would lead the way to a carbon-neutral circular economy that operates within the limits of the earth’s carrying capacity and biocapacity.

Although, the sustainability crisis is one of the greatest threats to our planet, solving it could – in the best case – create extraordinary well-being for humanity. The transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy will require an unprecedented renewal of all sectors of society. In the best case, societies would become more community-centred and fair and be places where all individuals and their solutions are important. In order to make this transition at a sufficient pace, we need to act on all levels – this means “top-down” methods as well as those that start at the grass-roots level.

Along with implementing solutions to the sustainability crisis, it is important to produce information and increase awareness of the long-term nature of the crisis. The direct impacts of the sustainability crisis already appear to be quite well known, but we need more research on the long-term, indirect and cumulative effects. What would happen if a disease epidemic and a heat wave both struck at the same time in a place where much of nature’s diversity had already been lost? Or what if the Gulf Stream reversed, bringing very cold conditions to Finland, and the global production of phosphorous ended simultaneously? The different knock-on effects of the sustainability crisis can have mutually reinforcing effects that we need to understand much better in order to prepare for them in the best possible way.

Ten proposals

Since the global sustainability crisis is a systemic challenge, its solutions must also be systemic. All sectors of society are needed to create solutions: governments, cities, companies, research and educational institutes, and individuals – and there must be co-operation between all of these.

The following section presents 10 ways that could help Finland and the other Nordic countries take responsibility for accelerating the required global transition. In this way, Finland could set an example for the rest of the world, move towards a carbon-neutral circular economy and simultaneously create more sustainable well-being for its people.

1. A MOVE FROM SILOS TO COMPREHENSIVE STRATEGY WORK

In order to solve the sustainability crisis, we need a comprehensive understanding of the root causes of the crisis and of the urgent need for solutions. Instead of focusing actions and strategies on a single policy area, public administration should move to comprehensive strategy work. The state administration must create an operating environment that produces and implements solutions to deal with the effects of the sustainability crisis while striving to solve its root causes, particularly at the international level. This can be achieved by raising the issue to the highest level of the state administration and making it a central part of co-operation between governments. Decision-making must also shift in a more scientific and information-based direction and the friction that still exists to a certain extent between decision-makers and researchers eliminated. State administration operators must learn to understand the scope of the worst effects of the sustainability crisis, the opportunities created by the markets and the urgent need for action.

2. MORE AMBITIOUS EMISSION REDUCTION TARGETS

The first full review of the Paris Agreement and stricter emission reduction targets should take place in 2018 because the climate crisis is progressing so quickly. The first review is scheduled for 2023, but this will be far too late. Accelerating the circular economy should already be made a key part of international climate agreements. At the same time, EU and Finnish climate targets must be updated to correspond to the targets of the Paris Agreement. Ambitious climate targets will promote the development of a favourable domestic market, which will then encourage companies to reduce their carbon footprint and increase their carbon handprint.

3. IMPLEMENT LOW-CARBON CIRCULAR ECONOMY SOLUTIONS

In order to solve the sustainability crisis, we need a rapid scaling up of existing solutions as well as new solutions. Since the timeline from research to widespread implementation is frustratingly long in comparison to the pace at which the sustainability crisis is progressing, it is important to fully utilise existing solutions to reduce emissions. State and municipal activities are particularly important because they handle the majority of public procurements.

4. PROMOTE DISRUPTIVE SOLUTIONS AND MARKET ACCESS

An innovative environment must be built to provide stronger support for the transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy. It should encourage the development of new, disruptive solutions. Public procurements should be directed at the implementation of existing sustainable solutions and new smart solutions. To support this, various risk-management mechanisms should be created to reduce the risks for procurement units when they use innovative and target-oriented procurement procedures, especially in the circular economy area.

5. INCREASE READINESS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR LIFELONG LEARNING

The transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy will eliminate old, familiar operating models and professions, but the sustainability crisis makes the change inevitable. This is why the transition has to be implemented fairly and equally in order to allow as many people as possible to find their place in the “new economy”. Lifelong learning and readiness for it will require strong development and support.

6. INVEST IN CITY INFRASTRUCTURE

City infrastructures must be harnessed to support the transition to a carbon-neutral circular economy. Economic steering methods, including fuel pricing, must be redirected. Incentives must be created to increase use of public transport and mobility services as well as daily physical activity. Another possibility is to share transport emission targets and the obligation for action at the regional level. Energy production in cities must be steered in an emission-free direction by promoting the implementation of renewable energy via processes such as public procurement.

7. STRENGTHEN CARBON SEQUESTRATION FROM THE ATMOSPHERE

Forests must be used better to control climate change by increasing carbon sinks and carbon stocks, such as long-term wood-based products. Maximising the value of wood and carbon stocks instead of the amount of wood use should be at the forefront of the national forest strategy. We must also ensure that forest diversity is retained and increased. In addition to forests, research and actions to maximise the carbon sink capacity of soils must be promoted. This will improve agricultural productivity at the same time.

8. CREATE A MORE SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEM

A sustainable food system will implement carbon-neutral circular economy principles and produce more diverse vegetarian food. Renewable energy production, nutrient cycling, elimination of waste, water management and digitisation are at the heart of a sustainable food system. A sustainable food system can be built piece by piece by developing sustainable regional solutions that can be scaled up based on the lessons learned. To create a sustainable food system, at least some of the current agricultural subsidies must be gradually changed to innovation subsidies. Agricultural policy should also encourage the implementation of new – especially digital – solutions in agriculture.

9. INVOLVE PEOPLE IN SOLVING THE SUSTAINABILITY CRISIS

We need to support responsible choices by households and consumers, and raise awareness of these choices. Sustainable lifestyles should be a part of the subject matter and teaching goals at all levels of education. Cities, state administrations and companies need to be encouraged to join in creating the conditions for more sustainable lifestyles; for example, online platforms where ordinary people can participate in developing a sustainable daily life. Communications and trials can inspire individuals to participate in solving the sustainability crisis.

Awareness of the sustainability crisis and its solutions can be raised among schoolchildren and students by creating new teaching units that deal with the sustainability crisis and circular economy. We need to develop a new type of teaching co-operation between the private and public sectors and between companies and schools.

10. CHANGE GOVERNMENT SUBSIDY MECHANISMS TO SUPPORT RENEWAL

The negative externalities of environmental and climate impacts must be taken into account when pricing energy and products: governments must find ways of reducing ineffective fossil fuel subsidies and increase the cost of polluting by penalising carbon emissions. Subsidy mechanisms and taxation should be seen as a single entity. Taxation should focus on placing higher taxes on things we want less of – such as climate and environmental pollution and overconsumption – and placing lower taxes on things that we want more of, such as services and products selected through the sustainable everyday choices of individuals.

Sources

[1] Stern, N.H.: The economics of climate change: the Stern review. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[2] NASA, NOAA Data Show 2016 Warmest Year on Record Globally, NASA, 2017.

[3] Rockström J., Gaffney O., Rogelj J., Meinshausen M., Nakicenovic N., Schellnhuber H.: A roadmap for rapid decarbonization. Science, Vol. 355, Issue 6331, s. 12691271, 24.3.2017.

[4] Peters, G. P. & Geden, O.: Catalysing a political shift from low to negative carbon. Nature Climate Change 7, 619–621, 2017.

[5] Rocha, M., Sferra, F., Schaeffer, M., Roming, N., Ancygier, A., Parra, P., Cantzler, J., Coimbra, A., Hare, B.:What does the Paris climate agreement mean for Finland and the European Union? Climate Analytics & Sitra, 2016

[6] Figueres, C., Schellnhuber, H.J., Whiteman, G., Rockström, J., Hobley, A. & Rahmstorf, S.: Three years to safeguard our climate. Nature 546, 593–595, 29.6.2017.

[7] Sitra: Kiertotalouden mahdollisuudet Suomelle [The opportunities for a circular economy for Finland], Sitra Studies 84, Sitra, 2014.