Africa is both a large and incredibly varied continent with diverse landscapes endowed with rich biodiversity. From 1,470-meter-deep Lake Tanganyika to Mount Kilimanjaro at 5,895 meters above sea level, the continent is home to a wide range of biomes and a plethora of species. Of the 50 countries with the most plant species, 22 are located in Africa. Some countries on the continent are megadiverse and host invaluable biodiversity hotspots with many species that are unique to African regions. For example, rooibos, a bush whose leaves are used to make a herbal tea, is unique to the Fynbos biome, which only covers a small part of the Western Cape province of South Africa.

Western Cape, South Africa. Image: Tim Forslund, Sitra.

Africa’s biodiversity faces many threats. These include unregulated agricultural expansion into forest, grassland and wetland ecosystems; deforestation and forest degradation; as well as pollution of oceans, lakes and rivers. Population growth has remained a major problem-tree causing much of this loss of biodiversity and in the process diminishing many ecosystem services which we are utterly dependent on, from food to clean air and water, flood control and climate regulation.

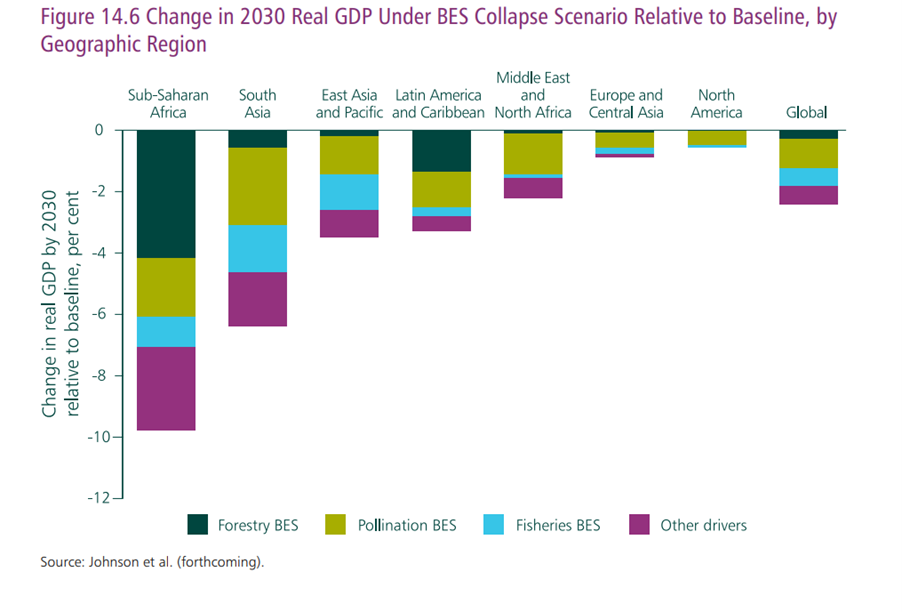

Africa is the continent that stands to lose the largest share of its GDP due to a depletion of biodiversity and ecosystem services already by 2030.

As a whole, the continent now faces the largest threats to its biodiversity out of any of the world’s continents. Under a business-as-usual scenario, Sub-Saharan Africa is the region that would experience the most severe biodiversity loss by 2050 – even 60% more than in Latin America, and 100% more than in Southeast Asia. This calls for some of the most urgent and far-reaching action. As the Dasgupta Review highlights (Fig. 14.6), Africa is the continent that stands to lose the largest share of its GDP due to a depletion of biodiversity and ecosystem services already by 2030.

The good news, according to Sitra’s study Tackling root causes – Halting biodiversity loss through the circular economy, is that we can also halt biodiversity loss already by 2035. Compared to the business-as-usual scenario, Africa is one of the continents that would see a significant biodiversity recovery under a circular transition. The study focuses on the four sectors with the largest impacts on global biodiversity and where a circular economy can play an important role. These sectors are food and agriculture, buildings and construction, textiles and fibres, and the forest sector. From the point of view of Africa’s biodiversity, there are three important ways in which the transition to a circular economy could take place:

- Resource-saving and regenerative production systems

- Space-efficient urban planning

- Reduced pressures on biodiversity from global consumption.

Interested? Read more in our article series.

1 Resource-saving and regenerative production systems

Sitra’s study highlights two ways through which a circular economy could benefit biodiversity outcomes: By reducing the pressure on nature from lower resource use and by regenerating the areas where we do produce our food, fibres and other materials.

Firstly, we can get more value from existing products and materials, from buildings to our food, clothes and other products. This is possible through long-lasting design, high use-rates through sharing and as-a-service models, lower input needs and active repair, reuse and recycling activities. These strategies all reduce our resource use and in turn the land area needed to produce them, leaving room for nature to thrive.

Actors across all corners of Africa already offer solutions which help make the circular economy a reality. In the southernmost part, the Western Cape Industrial Symbiosis Programme helps those with unused or residual resources connect with other companies that can find new value in these resources, while Safi Organics makes fertilisers through crop by-products in Kenya. In the most populous country of Africa, Nigeria, Cold Hubs helps avoid food loss in the first place, by providing solar-powered refrigerated buildings for farmers and retailers.

Secondly, as we can only reduce our resource use so much, it is important that we also support biodiversity in the areas where we produce things. This can be done through practices that are less extractive and instead work in harmony with – and like – nature to drive regenerative outcomes. In Sitra’s study, these practices, applied across the world’s fields, pastures and forests would together deliver 10% of the biodiversity improvement in the circular economy scenario. Besides enhancing biodiversity outcomes, the scenario suggests regenerative agriculture could enable a 30% reduction in the use of fertilisers – when the price of urea has increased by over 200% since 2020.

There is a plethora of practices that can deliver regenerative outcomes in support of biodiversity, soil health, yields and resilience. These practices vary significantly depending on the local context.

Recent studies show that combined use of compost and mineral fertilisers at smallholder farms in Ethiopia increased soil fertility and yield in some crops (e.g. Zeleke Asaye et al., 2022). One of the crops that originally comes from Ethiopia is coffee, a traditional cash crop. In Wonsho woreda in the Sidama Zone, it is intercropped with ensete, a staple food similar to plantain that also helps provide shade for the coffee, while honey, fruit and vegetables enable more diversified revenue streams for the farmers. Nurseries help deliver improved crop seeds that enable higher yields from each coffee bush, while terracing with rain harvesting pits reduce erosion and allow more of the precipitation to be captured.

2 Space-efficient urban planning

At a global level, built-up areas take up little more than 1% of land. Yet, as much as 40% of habitat loss today is due to infrastructure expansion. This is largely a result of a rapid urbanisation process, much of which takes place in highly biodiverse regions. The challenge related to urbanisation in many developing countries such as Ethiopia is that urban expansion is not properly planned and regulated with effective law enforcement. For example, while infill has been limited, urban areas in the outer zone of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia increased by a staggering 160% between 1989-2019, at the expense of green space, biodiversity and ecosystem services. For example, adjacent Wechecha forest has shrunk from a cover of 30% in 1973 to only 2.4% in 2013.

Additionally, urban expansion will largely take place on valuable cropland, 1.8-2.4% of will be lost by 2030 – 80% in Africa and Asia – largely on land that is almost twice as productive as the global average. Therefore, it is of critical importance both for biodiversity and food security that urban areas are planned to use as small an area as possible.

According to Sitra’s study, Sub-Saharan Africa, along with India, has the largest potential to increase its urban density by 2050.

According to Sitra’s study, Sub-Saharan Africa, along with India, has the largest potential to increase its urban density by 2050. There are already many good practices from China, Japan, Finland, Mexico and other countries how to best make use of urban space, from making use of existing land within cities, to constructing taller, multiuse buildings. Many of these practices could also play an important role in Africa’s cities in tandem with zoning and land-use regulations as well as building standards, but the solutions must be adapted with the local context in mind, as Africa’s urban sprawl largely differs from the suburbia of the Global North.

An added benefit of making better use of urban space would be more liveable cities with better access to services and higher productivity. For this purpose, high-quality public transportation systems adapted to the local context also play a key role. For example, in Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, a rapid transit bus system manged to cut average travel times by a full two hours a day! A study from Birmingham in the UK suggests that a similar bus system, by increasing connectivity, could increase the city’s effective population – those living inside an area reachable by a 30-minute bus ride from the centre – from 0.9 to 1.3 million, which could generate a 7% increase in GDP per capita from agglomeration benefits.

3 Reduced pressures on biodiversity from global consumption

Much of the Africa’s biodiversity loss is due to its own development and unsustainable use of biological resources. However, as highlighted in the Dasgupta Review, 26% of biodiversity impacts in Africa are driven by consumption happening in other parts of the world. Much of this biodiversity loss is due to deforestation to meet a growing demand for a few soft commodities – such as coffee, cacao, palm oil, beef and wood – for which the EU is introducing new legislation.

While trade can exacerbate deforestation, it can serve to drive a global circular transition and tackle biodiversity loss. IEEP, Sitra and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation recently published a report which highlights the important role EU free-trade agreements and co-operation could play to promote circular solutions.

We must work to reduce the total pressure on nature from consumption, in tandem with sustainable production. This is why the circular economy plays such an important role for biodiversity.

Ensuring sustainable production, such as regenerative agriculture, for key commodities under trade frameworks is of vital importance. However, unless the total global consumption of these commodities does not at the same time decrease, the risk is that deforestation continues outside the certified areas. Therefore, until all countries adhere to the same scheme, we must also work to reduce the total pressure on nature from consumption, in tandem with sustainable production. This is why the circular economy plays such an important role for biodiversity, as it addresses both production- as well as consumption-side interventions.

One way to reduce the total pressure on nature is to make products with fewer inputs and less waste. Today we use much of our agricultural land for animals rather than directly consuming what we grow. In fact, as much as 77% of agricultural land is used to feed or directly raise livestock. By reducing global meat consumption by half and dairy products by 67%, 350m ha of agricultural land – an area as large as DR Congo and Ethiopia combined – could be freed up by 2050.

Per capita meat consumption in Africa is already low, and most of the reduction would thus come from countries with high levels of meat consumption, where more plant-based alternatives are necessary. By reducing the land-use footprint, these countries can also reduce their pressure on Africa’s biodiversity. By contrast, in Africa the emphasis should be on ensuring that the meat that is produced puts less pressure on the continent’s nature, for example through more sustainable feeds. Some pioneers work with soldier fly larvae that consume organic waste and in turn are processed into a high-quality feed that can be used for poultry, fisheries and other industries. These include a project in Rwanda, South Africa’s AgriProtein and Ghana’s Neat Eco-Feeds.

Circular roots, circular future

Africa holds some of the world’s largest diversity – and biodiversity. It is a rapidly urbanising continent where most people retain roots in the countryside and in agriculture, with the logic of the circular economy – which works with and learns from nature – intuitive to most people across the continent. More than that, Africa is also the continent with the youngest population, which makes it well-placed to develop tomorrow’s technology-enabled circular solutions. As the continent facing some of the most severe threats to its natural richness, it also holds some the most important keys for solving the crisis and driving resilient growth across the continent. Nowhere is the future and the past more intertwined than in Africa. However, their convergence matters the most for the continent through their gaze at us calling for action here and now.